EODS Project

Digital Toolkit

About the Digital Toolkit

The EODS Toolkit outlines the EU Election Observation Missions’ (EOMs) methodological approach to analysing the digital ecosystem and supporting Social Media Analysts and Core Team members in assessing online campaigning, information manipulation, and digital trends through a consistent, and transparent framework. In line with the Guidelines on Observing Online Election Campaigns, endorsed under the Declaration of Principles for International Election Observation, the Toolkit strengthens the EU EOMs’ capacity to assess the online information environment effectively.

The Toolkit is:

Dynamic Web Source

A user-friendly platform providing guidance, key resources, and updated materials to support social media analysis, adaptable to rapid digital, legal, and technological changes.

Tailored Support for EU Election Missions

Step-by-step guidance for setting up Social Media Monitoring (SMM) projects during EU EOMs and guidance for experts in charge of digital landscape analysis during Election Expert Missions (EEMs) and Exploratory Missions (ExMs), to ensure an harmonized and consistent approach across missions.

Comprehensive Methodological Hub

A repository of public EODS documents and selected publications from the EU, OSCE/ODIHR, the UN, and major civil society organisations, promoting knowledge-sharing and best practices in the field of social media and elections.

Transparency Tool

This Digital Toolkit provides an overarching view of the European Union’s approach during Election Missions, enhancing transparency and fostering collaboration with other organisation

EODS Templates and Research Papers

Traditional and Social Media Monitoring

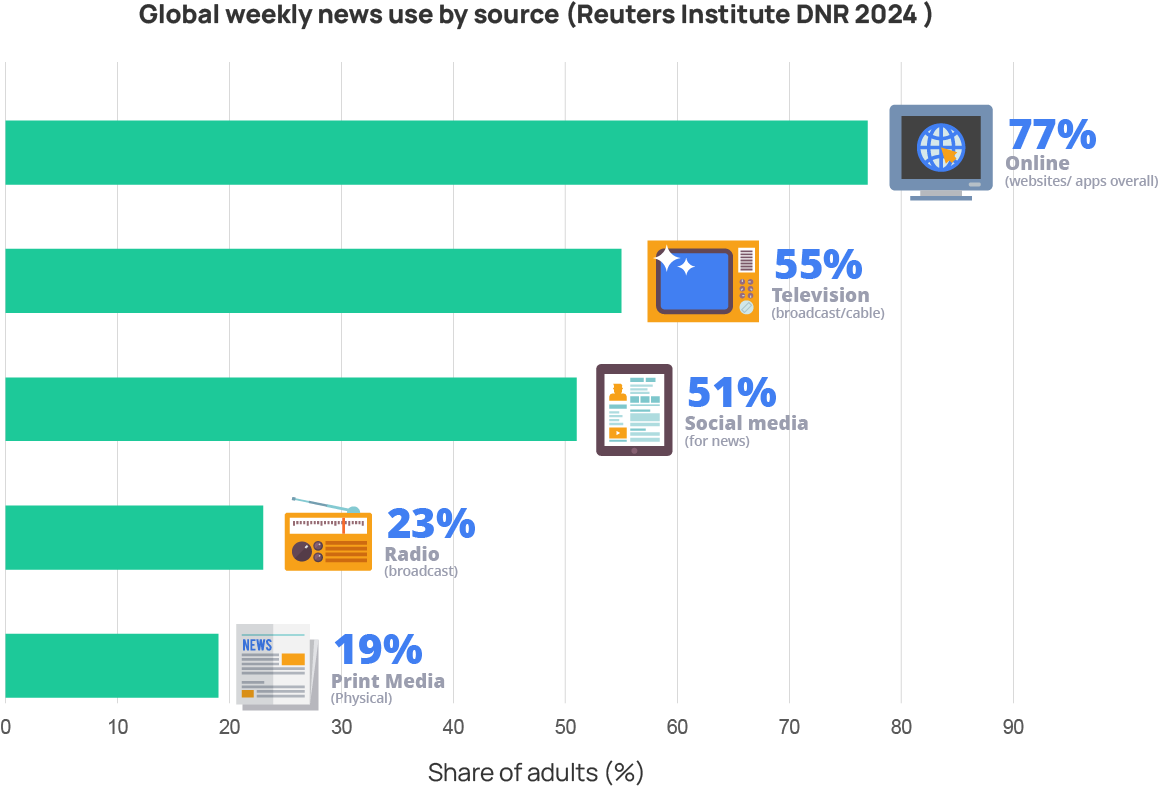

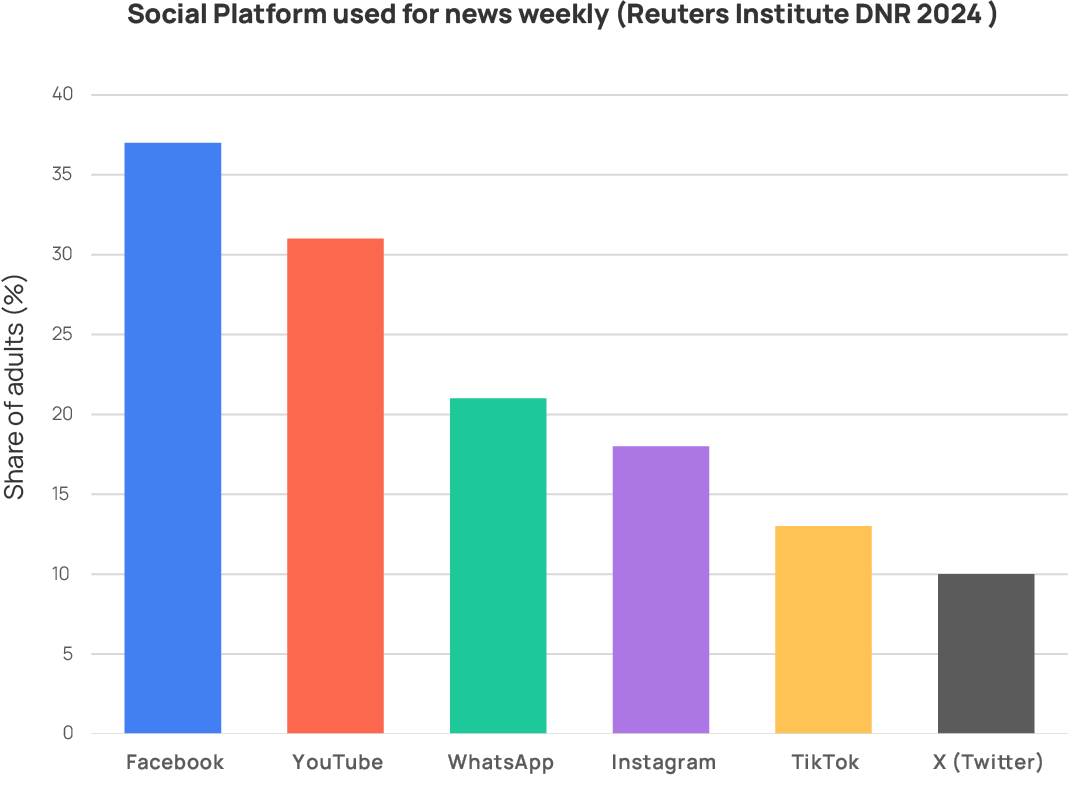

In line with the 2020 Joint Declaration on Freedom of Expression and Elections in the Digital Age by the EU Election Observation Missions (EU EOMs) assess both traditional and online media to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the electoral information environment. The coexistence and interaction between traditional and online platforms shape public discourse and influence voter perceptions during election campaigns (See charts below on global news consumption trends, including online platforms trends).

For this reason, EU EOMs operate through two complementary analytical components: the Traditional Media Monitoring Unit (TMMU) and the Social Media Monitoring Unit (SMMU). The TMMU assesses pluralism, balance and access in print, radio and television including news web-sites and social media accounts of national media outlets. The SMMU analyses online political communication, campaign dynamics and the circulation of information ononline platforms.

Together, these units provide a comprehensive, methodologically coherent assessment of how information flows across media ecosystems, strengthening the mission’s capacity to evaluate the integrity and inclusiveness of electoral processes in the digital age.

EU EOM CORE TEAM ONLINE CONTENT ANALYSIS

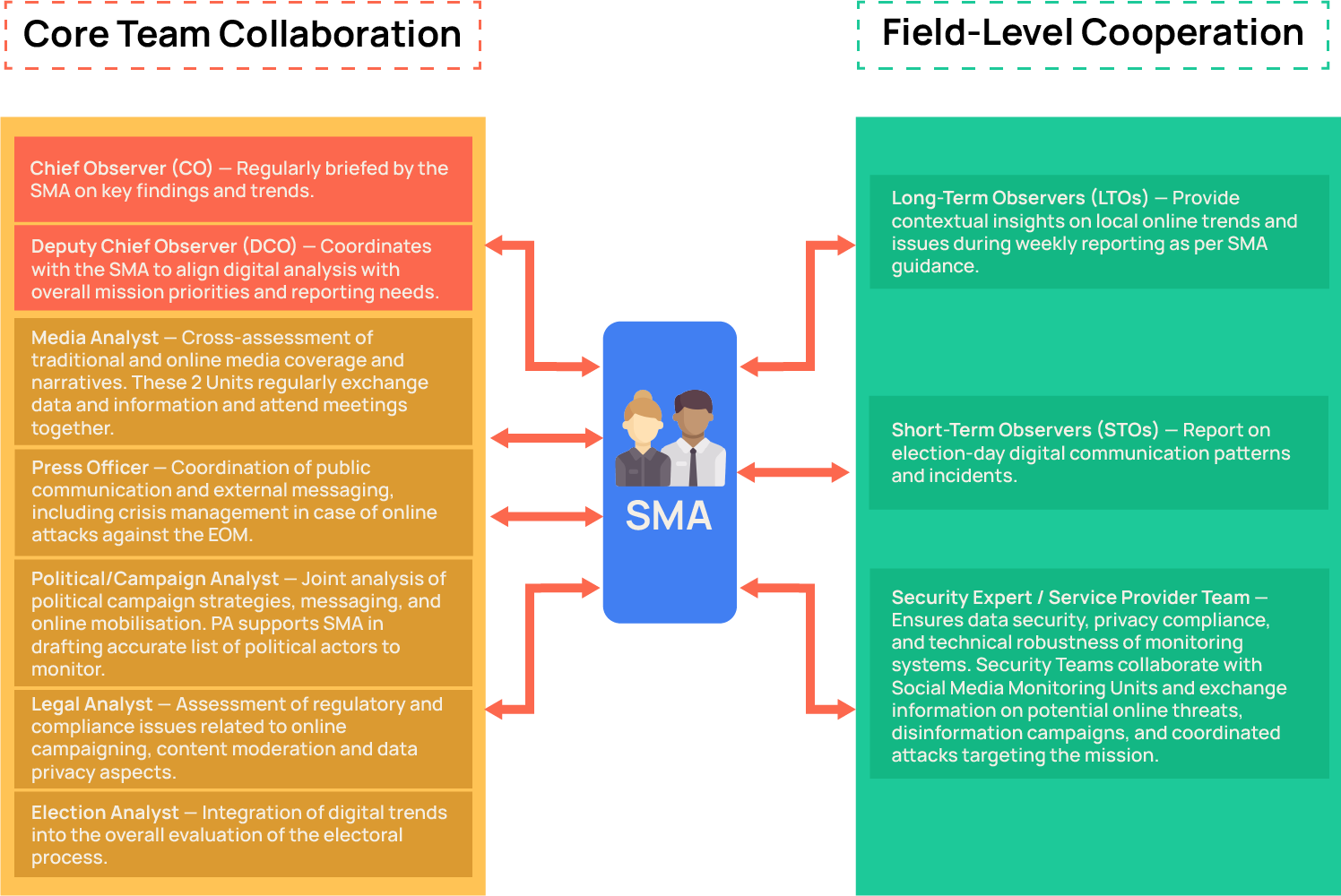

The monitoring and analysis of online election-related content is led by the Social Media Analyst (SMA)

The SMA has overall responsibility for this component; however, the analysis of digital election content is a cross-cutting task that benefits from the expertise of the Media Analyst (MA), the Press Officer (PO) and all Core Team (CT) analysts.

The SMA ensures regular collaboration and information exchange with each member of the Core Team to maintain an integrated, coherent analytical approach for EU Mission reporting.

Project Set-up

Online campaigning is increasingly important worldwide, as citizens rely more on digital channels for electoral information and candidates use them to reach voters. These channels include online news outlets, party and candidate websites, and, above all, online media platforms, now a major source of election news. For this reason, social media monitoring has become an essential part of election observation.

What is social media monitoring during EU Missions?

Social media monitoring refers to the process of collecting, analyzing, and visualizing trends and activities occurring on social media platforms. It involves using tools and techniques to collect data about hashtags, keywords, and political and electoral actors behavior across online platforms like Facebook, X, Instagram, Tik Tok.

The EU Social Media Monitoring (SMM) methodology is designed for EU election observation missions to monitor social media platforms systematically. It collects and analyzes election-related content to provide consistent, objective data on the role of social media in the electoral process. These findings form the basis for EU EOM Final Report and Recommendations to stakeholders.

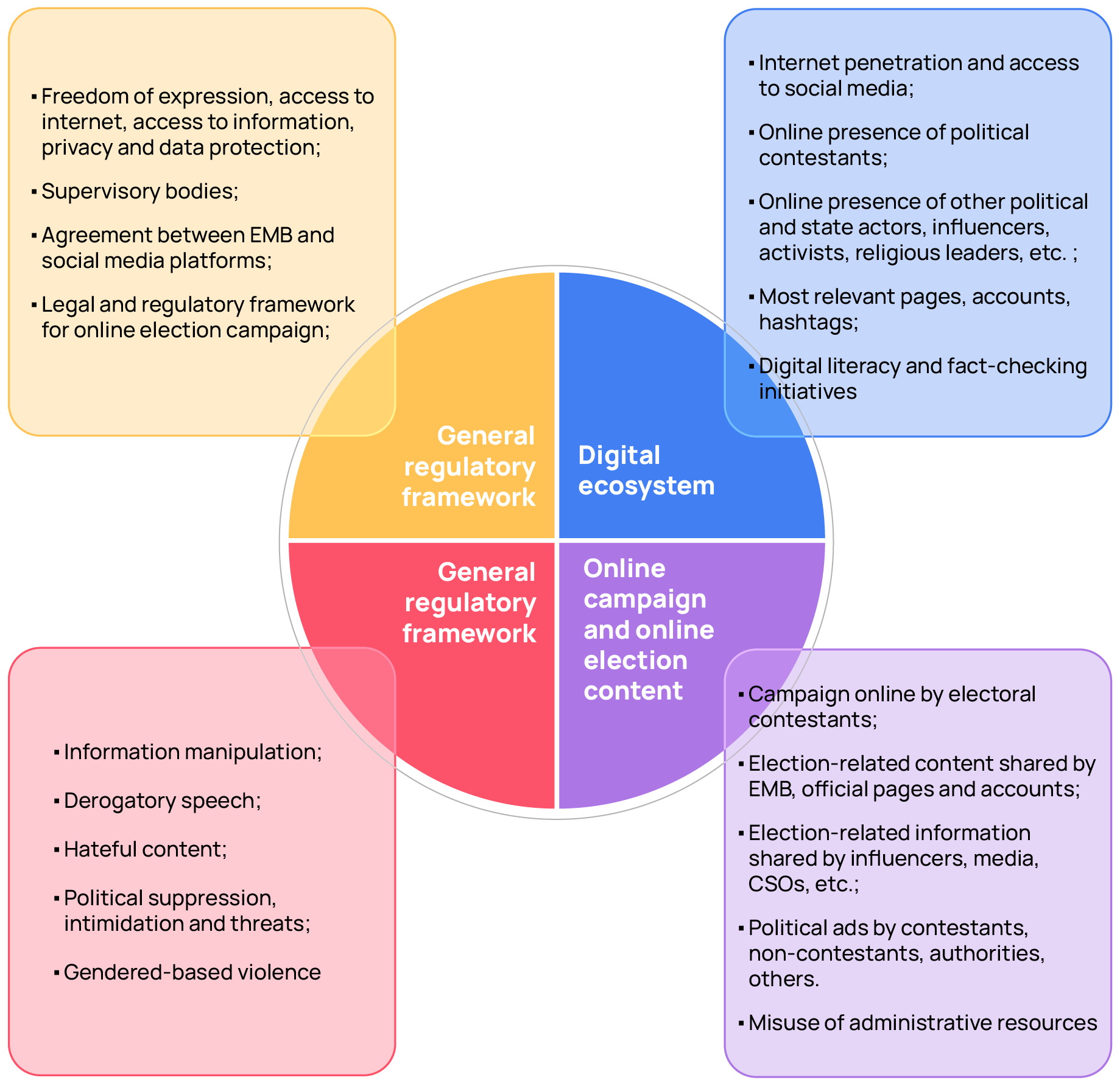

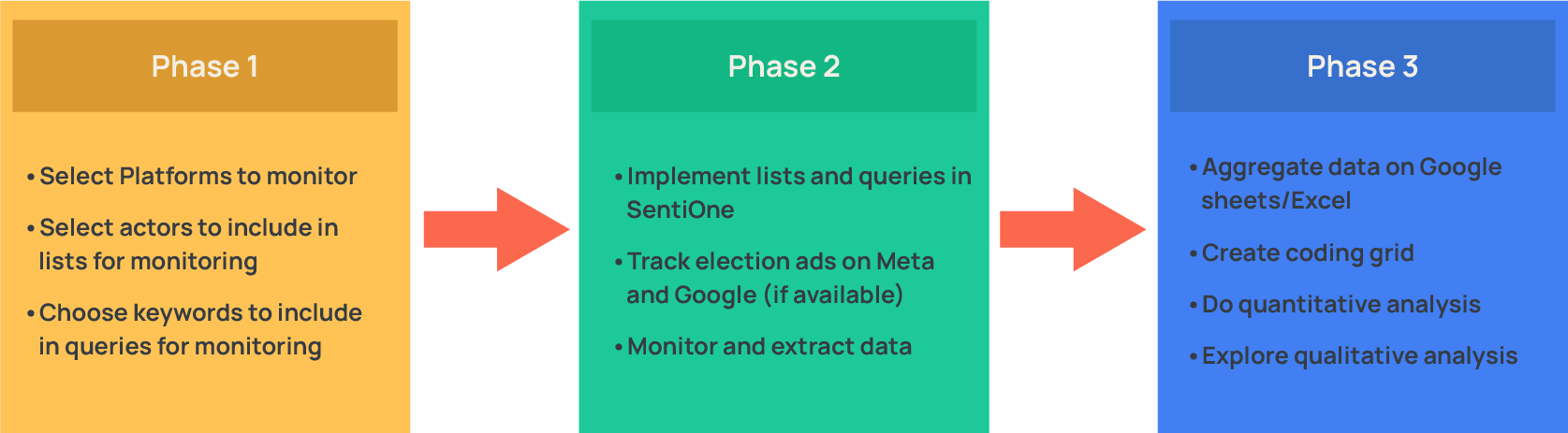

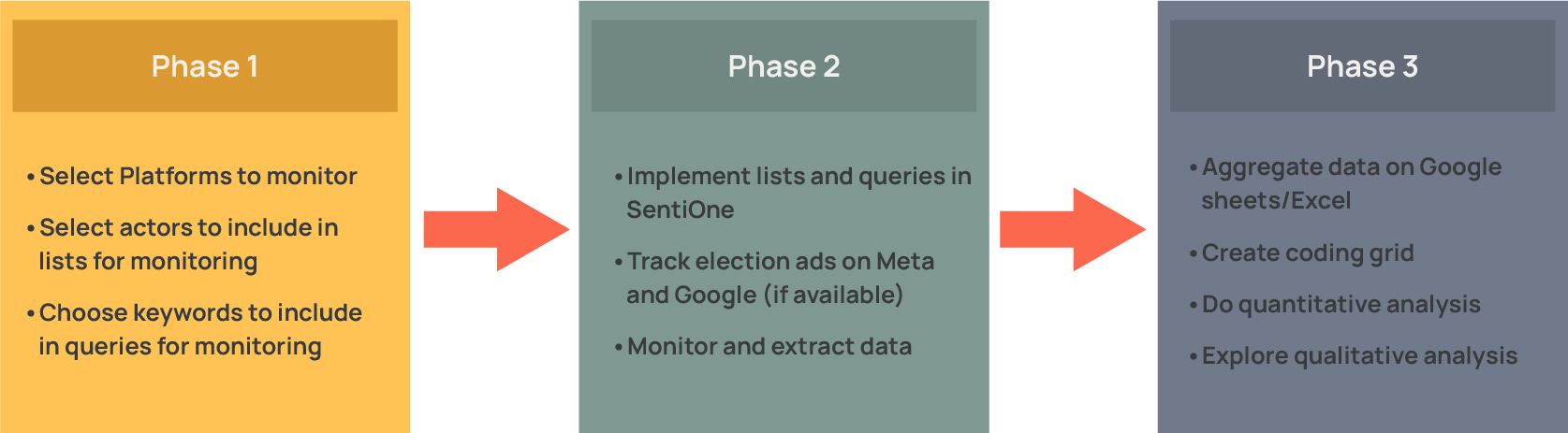

The chart below helps the experts to establish a framework for observing election-related content online:

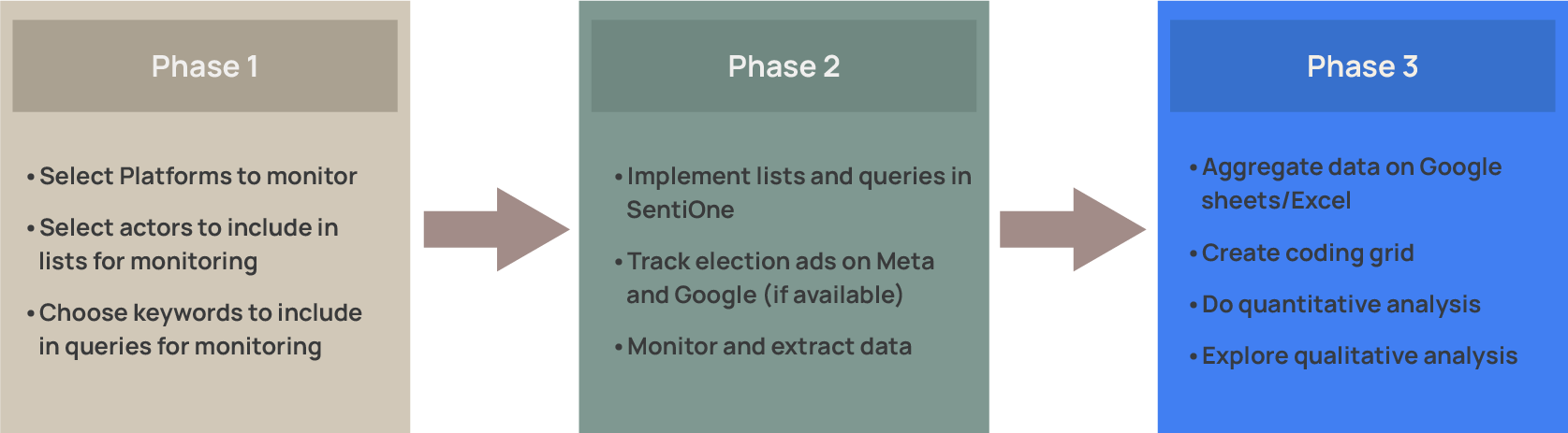

The implementation of the EOM/EEM social media monitoring project develops along 3 phases:

Mapping Online Environment

DESK REVIEW

The DESK REVIEW is the first step to understand the country’s online information environment.

The free tools in this section will allow EEAS Policy Officers and Election Missions Teams to begin mapping the digital and media landscape, offering quick insights into platforms, narratives, and trends relevant to the national context. They are particularly useful for pre-mission preparation or when exploring new country contexts.

For accurate and comparable results, ensure that each search is guided by a clearly defined topic (e.g., political actor, electoral issue, or policy debate).

- Datareportal latest stats

- Datareportal latest country stats

- Statista stats

- Napoleon Cat stats

- Emplifi industry benchmarks

- Latest Digital News Report

- Digital News Report country data

- Google Search is considered a valuable tool for exploratory analysis.

- Google Trends provides info about trends in Google Search.

Why a Checklist for Social Media and CT Analysts (ExM, EEM, EOM)?

A checklist is essentially a structured set of questions for Social Media Analysts (SMAs) and other Experts deployed in Election Observation Missions (EOMs), Election Expert Missions (EEMs), and Election Exploratory Missions (ExMs). Its purpose is to ensure a systematic, consistent, and comprehensive approach when engaging with interlocutors and key election stakeholders.

The following check-list is organized by 9 thematic areas:

- Is there an ownership concentration over Internet Service Providers (ISPs)? If yes, how does it affect access to the internet? If not, how are the legal, regulatory, or economic conditions for becoming an ISP? Are registration requirements for ISPs and any other access providers approved/rejected on partisan or prejudicial grounds?

- What is the legal and regulatory regime for Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) infrastructure?

- To what extent do infrastructural and economic limitations restrict access to the internet?

- Does the primary legislation, including, but not limited to, anti-terrorism legislation, defamation laws, cyber security laws, conform with international standards for freedom of expression? For example, does the legal framework include criminal liability for online defamation or insult of state officials? Are restrictions over online content transparent, proportional to the pursued aims, and appealable through an independent and fair mechanism?

- Are online journalists, bloggers, or other content providers sued, prosecuted, jailed, or fined for their publications? If so, is their right to effective remedy and due process respected? Are they subject to extra-legal intimidation? Is such a legislative framework conducive to self-censorship online?

- Is the online environment providing for a diversity of sources of information, a variety of contents, ideas and views?

- Does the country have a data protection regime? Does the national law on data protection apply to the data collected and used (processed) by political parties and other political actors? Does it sufficiently protect voters’ data against commercial and political exploitation?

- Is there a privacy regulator? Are privacy regulators independent from political interference? Are they sufficiently resourced? Do they have sufficient enforcement powers (such as the ability to issue substantial fines)? Is the decision-making process transparent and subject to a judicial review?

- Is there any history of data breach or data being exposed in the country, especially during election periods? How did authorities, EMB, parties respond?

- Do political parties and other political actors have data protection policies? Do they disclose where they get the personal voters’ data from and what they do with it?

- Have political parties, third parties and other relevant actors obtained consent for the individuals prior using their data or how else do they justify holding the data? Is there an option to opt out for users?

- Is profiling, microtargeting, artificial intelligence/machine learning used in the campaign?

- Do private companies work on applications using personal data by request of the EMB? Is the privacy of this data guaranteed?

- Are political parties granted access to electronic voters’ registers or biometric databases? Is this access granted with respect for privacy rights?

- Are voters aware of the use of personal data and trained to protect personal data?

- Do EMB have effective procedures in place to prevent or respond to information manipulation operations that risk harming the integrity or functionality of the process?

- Are the relevant members of the EMB adequately trained to understand the challenges posed in the online environment?

- Does the EMB conduct any social media monitoring activities?

- Does the EMB or other relevant state authorities have established any form of cooperation with the social media platforms? If yes, what does it entail? How formal is such an agreement?

- Does the EMB resort to the Internet and social media platforms to conduct voter information and civic education campaigns? Do social media platforms support such efforts? If yes, how do platforms contribute to educating voters and disseminating election-related information online?

- Does the EMB publish information of public interest (decisions, election calendar, polling stations results, etc.) on their website and social media accounts? Is such information comprehensive, accurate, non-partisan and easy to access? What is the level of interactivity for users provided by the web tools used by EMB?

- Does the EMB use social media platforms to provide specific assistance to users via online Q&A or special hashtags for voters to ask questions to the EMB?

- Does Google, Facebook and Twitter have an in-country contact person/office/content moderation team? What mechanism is available for reporting abuse and addressing complaints? From which regional or international office do the relevant tech companies cover the host country (if an in-country team is not present)?

- What is the internet penetration, digital and media literacy rate in the host country? How many users are registered for each social media platform and what is the reach of other online platforms? What type of pages/accounts have the largest audiences? What is the relevance of closed groups and instant messaging in political communication? What is the dominant language used on social media platforms?

- Who are key bloggers/influencers/discussion groups setting the agenda on social, political and election-related topics? Do they support/oppose a particular electoral contestant?

- Do the government/public institutions/executive-level state officials use the Internet and social media platforms to communicate with citizens? Do they publish information of public interest online? Are they required to publish it? Is published content non-partisan or rather is it instrumental to campaign or propaganda purposes?

- Are civil society organisations (CSOs) using online communication tools to mobilise and inform voters on relevant matters regarding the elections? Do CSOs use social platforms and online tools to monitor state institutions at central and local level? Do CSO use crowdsourcing and other cooperative online tools to observe elections and report on incidents, malfunctions and alleged frauds?

- Are media and digital literacy rates developed enough to allow citizens to fully exploit the use of the Internet? Are relevant state authorities, civil society or tech companies implementing programmes to raise digital and media literacy?

- Is campaigning online regulated by electoral legislation and/or by supplementary regulations, issued by the EMB or another state authority (for example, by a regulator)? Is there a voluntary code of conduct governing the conduct of political parties and candidates during the campaign period? Are prohibitions on hate speech, discrimination, and information manipulation featured in the code of conduct?

- Are there any regulations regarding campaign silence online? Do social media platforms respect such provisions (if any)? Is there a paid political campaign ongoing on platforms during the campaign silence? Are any measures taken either by the platforms or by EMB and other competent authorities against paid campaigns during the campaign silence?

- Are there any regulations related to the publication of opinion/exit polls? Do online platforms respect such provisions? Are opinion polls pushed across digital platforms in the form of sponsored content?

- Has artificial intelligence been deployed to harm candidates? If so, are there initiatives educating the public on the risks of doctored material, including video or audio material?

- What is the online presence of electoral contestants (how many followers they have, which platforms they use, etc)? What are the campaign strategies online? In which ways political actors engage with voters, and which are the online campaign tools and the data they use in their campaigns? What are the contents, topics, tone, and the type of interaction they adopt to communicate online?

- Are political contestants resorting to information manipulation techniques (bots, trolling, fake accounts, search engine manipulation, etc.) to campaign?

- Are electoral contestants using other digital campaign tools, such as direct messaging or mobile applications for campaign purposes, including on E-day?

- Are political campaigns online targeting any particular ethnic or religious group in both, a positive or a discriminatory way? Are political campaigns online encouraging participation by women, persons with disabilities and other vulnerable groups? Are there campaigns, including online harassment, doxxing, astroturfing of demeaning information, that discourage their participation in the elections?

- Are third parties campaigning for or against a certain candidate? If so, what messages do such campaigns promote? What campaign methods do they employ; do they include sponsored content?

- Are state institutions and executive-level public officials campaigning for or against a certain candidate from their official social media accounts? Do such campaigns (if any) also include sponsored content and political advertisement? Who benefits from such campaigns?

- Have parties signed codes of conduct for avoiding inflammatory language (etc.) in the social media during the campaign?

- Are there any legal provisions outlawing the distribution of content deemed harmful? If so which kind of contents are included, are definitions of such content clearly stipulated in the law? What penalties are foreseen for spreading such content? Are detentions and prosecutions on such charges carried out in a non-discriminatory manner or are they used to silence voices of dissent?

- Is there evidence of coordinated and automated information operations (e.g. bots used to amplify messages and contents related to elections)? Is there evidence of trolls and human curated fake accounts being used in the campaign?

- Is there evidence of coordinated information manipulation campaigns aiming at discrediting a certain political actor, EMB or to undermine the integrity of the electoral process as a whole? Which channels are being used to disseminate manipulated information? What policies do platforms have to monitor/downrank such content?

- Are there accounts/pages that promote violence, sow discord or propagate discrimination? If yes, how large are their audiences? Is the content originating from such accounts/pages shared by electoral contestants? Is there any instance of such content being shared by print and broadcast media outlets? Is such content pushed across various platforms in a form of sponsored content?

- Are there electoral contestants that use hateful content/derogatory speech and/or spread disinformation on their official accounts? Do candidates and parties contribute to inflaming the campaign rhetoric on the web or rather they tend to moderate views and comments posted? Are EMB or other relevant state authorities taking any measures against such electoral contestants?

- Is there a suppression of credible news? If yes, what kind of news do such campaigns aim to discredit?

- What initiatives exist in the host country to fight disinformation and hateful content? Are they state-sponsored, promoted by civil society or other entities or by social media platforms? If there are fact-checking initiatives, are they credible and nonpartisan? Is there a cooperation between fact-checking initiatives and mainstream media? Do social networks cooperate with fact-checking services/initiatives? Are these initiatives professional/efficient? Have organisations working on fact-checking projects been accredited by international networks of fact-checkers, such as the Poynter Institute?

- Are social networks offering its users any technological solutions to disinformation and harmful content which users may apply on a voluntary basis?

- Are there any initiatives monitoring hateful content and derogatory speech and information manipulation levels during the elections?

- Is online political advertisement and issue-based advertisement defined and regulated in law and/or in regulations governing the campaign? Who is to oversee the compliance with the law and respective regulations? Is the oversight effective, are technical, human, and financial resources sufficient? Is the EMB or other regulatory institution monitoring campaign spending by candidates on social networks?

- Are there any legally binding reporting and disclosure requirements for electoral contestants? Who is to oversee the compliance with those requirements? How detailed are those requirements? Within which timescale? What are the sanctions for failing to comply? Are electoral contestants actually disclosing their online campaigning expenditures with sufficient detail to allow for a proper oversight?

- Are there any reporting and disclosure requirements for service providers, such as media, advertising agencies and tech companies? If not, do tech companies voluntarily report on such spending? Is such information available for regulatory bodies only, or also for the public? In what level of detail?

- Is information related to party and campaign finance, including lists of donors and disaggregated reports on campaign expenditures, published online? If yes, is such information published in a format that grants easy and prompt access to such information to the general population?

- Is the third-party campaign permitted in the host country? Is third-party campaigning in a form of sponsored content and paid advertisement observed? Would expenditures related to it factor in electoral contestant’s campaign spending? Are there any limitations on such third-party spending?

- Have the main Internet platforms operating in the host country developed policies for transparency of political ads and other political communications, and transparency of targeting? Is Facebook’s Ad Library fully rolled out for the host country? Is information about ads restricted to only those paid by contestants, or such information is also available for content sponsored by third parties?

- Is there a legal requirement to clearly label all political advertising as such? If so, is this rule respected online? Is there a legal requirement to display information about who sponsored the political advertising? If so, is this rule respected online? Are platforms adopting appropriate and efficient measures to ensure that political ads are clearly distinguishable and are readily recognisable as a paid-for communication or labelled as such?

- How important is social media in your campaign strategy compared with traditional media?

- Which online platforms (e.g., Facebook, X/Twitter, Instagram, TikTok) are most effective for reaching your target audience?

- What are your key objectives for online campaigning : visibility, voter mobilisation, fundraising, or shaping public debate?

- Do you use data analytics, targeted advertising, or influencers to reach specific voter groups?

- How do you ensure compliance with national regulations on online campaigning and paid advertising?

- Have you faced or observed disinformation, smear campaigns, or coordinated manipulation online? If so, how do you respond?

- What measures do you take to protect your candidates and supporters from online harassment, hate speech, or privacy violations?

- How do you manage your social media content: is it handled internally or by external consultants?

- Are women candidates and minority representatives in your party equally visible and active online?

- How would you describe the tone of the online campaign environment — more open and pluralistic, or more polarized and aggressive?

- Do you believe social media has improved citizens’ access to information, or does it risk spreading misinformation?

- How does online campaigning influence your relationship with traditional media and journalists?

- How would you describe your access to traditional media during the campaign: equitable, limited, or influenced by ownership and affiliations?

- Do you feel that television, radio, and print outlets provide fair and balanced coverage of your campaign?

- Have you been invited to participate in debates, interviews, or election-focused programmes? If not, what barriers have you faced?

- Are you satisfied with the access, cost, and transparency of paid political advertising?

- Have you experienced any bias, editorial restrictions, or forms of indirect pressure from media outlets?

- How do you evaluate the coverage of women candidates, minority groups, and smaller parties in traditional media?

- Do you believe public/state media fulfil their obligation to provide balanced and impartial information?

- Have you filed or considered filing any complaints related to media coverage or access?

- How do you view the interaction between traditional and online media in shaping voter opinion?

- Overall, how would you rate the fairness, accuracy, and professionalism of media coverage during this campaign?

Setting Up Social Media Monitoring Projects

Assessing election processes on social media requires a solid methodology to ensure that observations, conclusions, and recommendations in the final report are objective and evidence-based. Findings should not appear subjective or discretionary, but supported by verifiable data and reproducible methods. To achieve this, a Monitoring Project must be built on 3 main pillars:

Social Media Methodological Framework

The SMM Framework provides a quantitative/descriptive analysis and a qualitative/explanatory analysis. The quantitative data from social media feeds a qualitative analysis of the role, reach or nature of the discourse on social media.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Identify the most relevant social media platforms in the country of the mission:

- Research which are the social media platforms with most users;

- Assess the prevalence of political and electoral content on those platforms, Some may have a large number of users but scarce political content;

- Analyse the existence of tools to monitor content on those platforms;

- Choose 3 to 5 platforms, depending on the capacity of your team;

- WhatsApp and other messaging platforms are out of scope due to data protection and privacy issues.

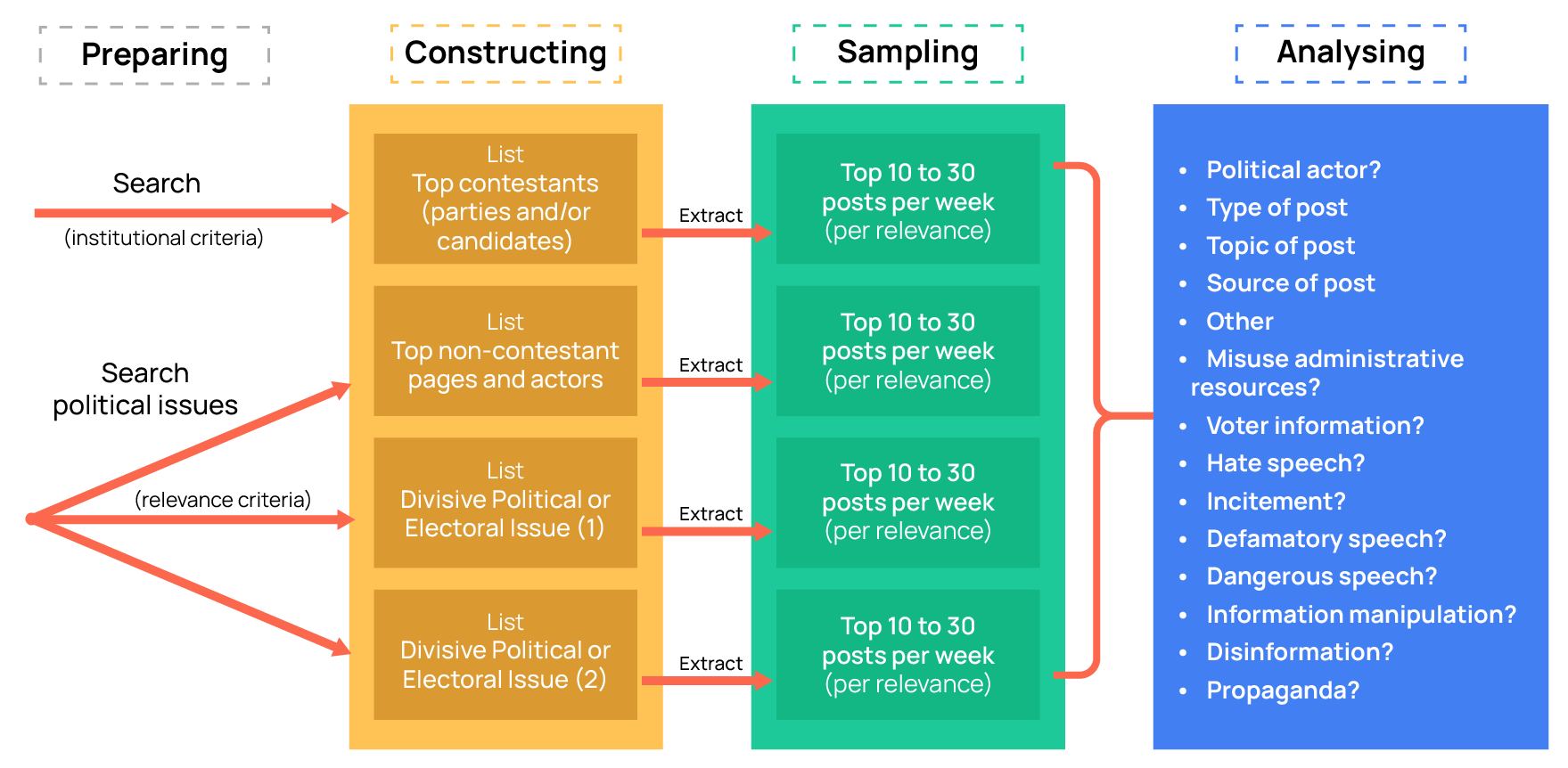

Develop and implement a Framework for collecting and analysing data (see proposed framework below):

- Establish lists of relevant social media actors to monitor;

- Establish search queries around relevant sets of keywords;

- Extract the most relevant posts in each list and query and analyse them as a significant sample

Construct the monitoring lists and queries by:

- Selecting institutional actors according to their institutional role (official candidates and/or governmental actors);

- Select third-party accounts with political relevance (previously assessing that political relevance)

- Create search queries for the divisive or polarising issues (e.g., derogatory language; racism) using the same procedure. When identifying sensitive or high-risk topics (‘triggers’), SMAs should keep in mind the four areas of assessment set out in this toolkit: online campaigning, online political advertising, information manipulation, and Derogatory Speech and/or Hateful Content. Topics that are likely to generate problems in any of these areas (for example, narratives about voting procedures, polarising identity-based issues, or online harassment of candidates) should be flagged early and monitored throughout the mission

- Construct a significant sample of posts to analyse. Select which posts to analyse by ordering posts by impact in each timeframe (e.g., 10 posts per week, 30 postsper month).

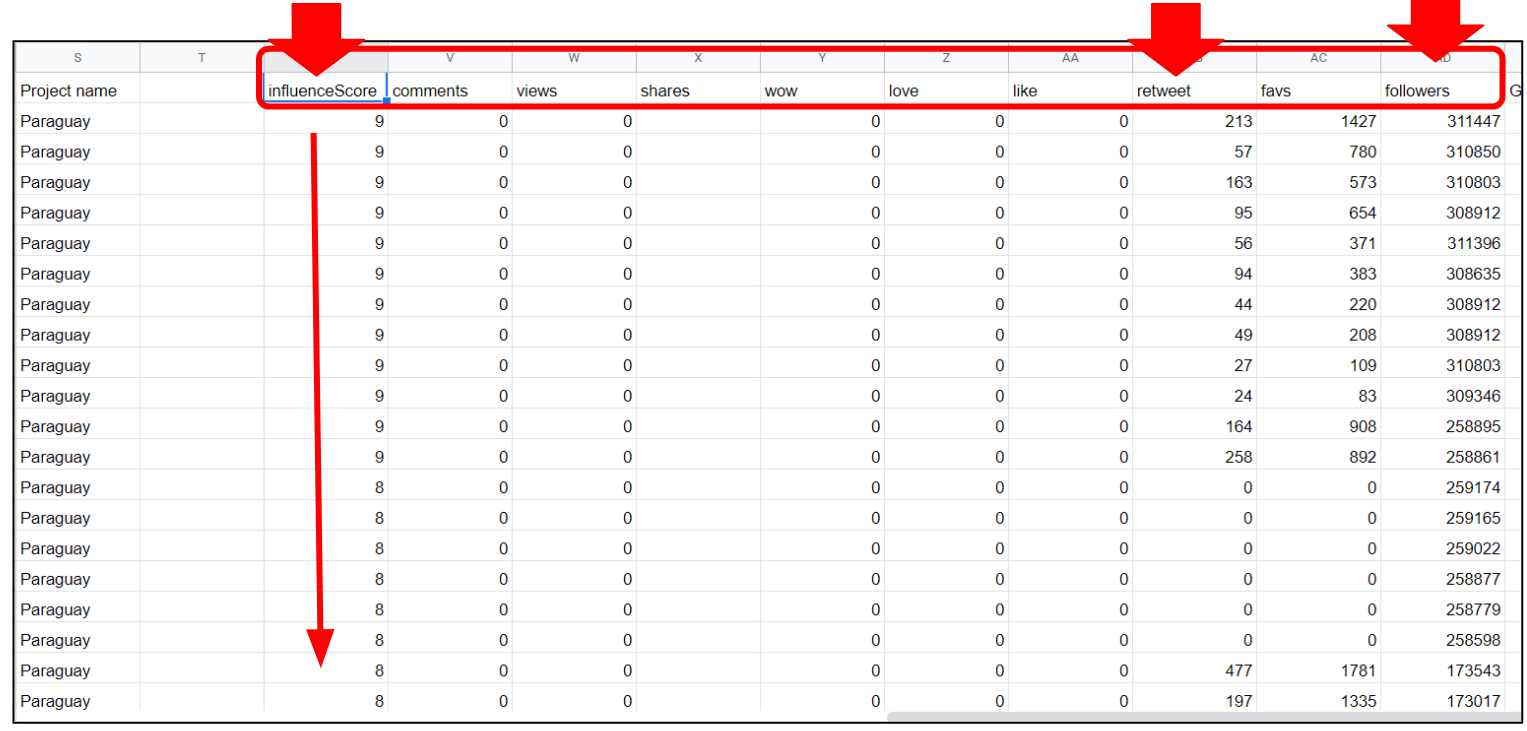

In this toolkit, we use online impact as a shorthand for the combined effect of reach, engagement and virality of a piece of content or an actor’s activity. On each platform, the Social Media Analyst should identify which available metric (for example, views, impressions, interactions or an influence score) is the best proxy for online impact. This metric will be used as the relevance criterion when sampling posts and actors for qualitative analysis.

FRAMEWORK FOR EOMs to construct “significant” lists of actors and “significant” samples of data:

NOTE: This is a proposal. It should be adjusted to local context.

Before starting regular data collection, the SMA should establish baseline or “normal” levels of online impact for the main platforms and actor categories in the country. Using the desk-review tools (see Phase 1.1 – Desk review – main tools) and an initial exploration of key accounts (candidates, parties, major news outlets, influential third-party pages), the SMA should estimate, for each platform:

- Typical ranges of followers for these actors;

- Typical ranges of interactions per post (reactions, comments, shares);

- Typical ranges of views or impressions for posts and videos.

These baselines allow the mission to distinguish between normal content (within the usual range of online impact for that actor), high-impact content (significantly above the usual range) and viral content (high-impact content that also spreads unusually quickly or across platforms). Because online audiences vary greatly between countries, the same absolute number (for example, three million views on a video) may be exceptional in one context and common in another. Each mission should therefore define its own low/medium/high/viral bands for online impact and use them consistently in the analysis.

This methodological framework is designed to highlight the RELEVANCE of the publications as its primary focus. When thinking about the potential impact of each piece of social media content (posts, photos, videos, etc), we must take into account how many people contacted or interacted with that content, because that contact or interaction is a measure of the attention being paid to it. If only 100 people saw a given piece of content, that piece of content is less influential than another piece of content that was seen or interacted with by 100.000 people. That's why the methodological framework includes the relevance of the publications - usually measured by views or interactions - as its mains focus.

Selecting platforms to monitor

Questions to be answered:

- Which social media platforms are most relevant?

- Which are most used by which age groups and social/political actors?

- Which are more prone to information manipulation and/or derogatory language?

- Is information manipulation prevalent? On which platforms?

- Is the Facebook Ad Library available? Do candidates or supporters use political ads?

- Is Derogatory Speech and Hateful Content an issue? On which platforms? Towards which groups?

- Do government and electoral bodies have social media presence?

- Are political influencers active on social media? If so, on which platforms?

Sources:

Use the tools described in Desk review – main tools, combined with:

» Exploratory searches on the platforms themselves

» social listening tools (when available)

» Consult with local stakeholders

NOTE: EEMs use the same Phase-1 guiding questions and sources as outlined in the ‘Phase 1 – Mapping the online environment’ section of this Toolkit, but typically limit monitoring to a maximum of two platforms and do not implement keyword queries unless explicitly requested

Selecting actors to include in the lists

Prepare and construct lists of top institutional pages and actors

Go to candidates' websites and track their presence on social media. Register the URL and the number of followers on a Google sheet of Excel file for future reference.

Whenever possible, try to use institutional criteria, like the official list of election candidates or the list of parties with seats in the parliament.

Prepare and construct lists of top non-institutional pages and actors

Search and track the most relevant pages or accounts talking about the election, including political influencers or political pages not running in the election. Register the URL and the number of followers on a Google sheet of Excel file for future reference. Use keywords related to the election or the political situation and try to identify public accounts or pages, either personal or non personal, with significant followings and predominant political content.

Choosing keywords to include in queries

Search for political and electoral issues using keywords that are relevant to the election. If necessary, consult with local stakeholders to identify 5 to 10 initial keywords.

Then run those keywords in Google search, Google Trends, social media platforms and social media listening tools to identify other words that are used in relation to those and choose the ones that are most relevant (most used and most directly related to the election). Pay special attention to other search suggestions on Google Search and Google Trends

You may want to use boolean search operators to perform the search and to construct the query.

Consider creating at least two queries:

- one directly related to the election (the name of the candidates or parties in the election is a good possibility);

- one related to a polarizing/divisive issue relevant in the election (eg: ethnic/racial divides; corruption; immigration, etc). Consult with local stakeholders to pinpoint these issues. If there are more than one divisive/polarizing issue, consider two independent queries of this type. This kind of search queries tend to surface the most problematic content regarding information manipulation and/or derogatory speech.

Analytical Framework

4 AREAS OF ASSESSMENT

The analytical framework of this Toolkit is built around four areas of assessment that apply to all mission types (ExM, EEM and EOM): online campaigning, online political advertising, information manipulation, and derogatory or hateful content. These areas provide the main lenses for understanding how digital communication affects electoral integrity and fundamental rights.

Each area is linked to specific international standards, such as freedom of expression, equality and non-discrimination, transparency and the right to political participation (see International Standards table below). Across all four areas, observers should consider not only what is happening, but also:

- its online impact (how visible, engaging or viral it is); and

- its potential harm (how seriously it may affect rights, participation, safety or trust in the process).

The following subsections briefly define each area of assessment and show how they relate to broader international standards. Detailed guidance on data collection and analysis is provided in Phase 2 and in the “Online campaign: Analysis and Research” section.

The Toolkit identifies the four areas of assessment and provides specific guidance on how to monitor content on social media platforms to produce a solid analysis. These four main areas include:

Online Campaign

by electoral contestants and other stakeholders

Political Advertising

placed on online platforms by electoral contestants and other stakeholders

Information manipulation

efforts identified including coordinated (in)authentic behaviour

Derogatory speech

and possible instances of hateful content spread during the election campaign

1 - Online Campaigning

In this area of assessment, the goal is to monitor how party and candidate accounts use social media during the election to carry out their campaign online. This area focuses on their organic communication (posts, comments, interactions) across platforms. Paid or sponsored online content is covered separately under the Political Advertising area of assessment.

The sample for this area of observation should be all social media posts per candidate and party in a defined timeframe. Although, some threshold to limit the scope may be required. In the cases when the number of candidates/parties and the total posts per per candidate/party per week exceeds the capacity of the team, try to observe primarily the most relevant publications for all candidates/parties or for each candidate/party (see Methodological frameworks section for reference).

Given the data available to researchers, see the possible research areas:

- Social media usage per candidate/party

- Top social media platforms used for campaigning

- User engagement with party/candidate accounts

- Use of negative or positive campaigning techniques by parties/candidates (define 'negative' carefully and with sense)

- Topics discussed by party/candidates

- False claims or Derogatory Speech and Hateful Content threatening electoral integrity

Consider cross-referencing sections on “Information Manipulation” and “Derogatory Speech and Hateful Content” to understand if such harmful techniques are being used by official party or candidate accounts.

For step-by-step guidance on sampling, data collection and analysis of party and candidate accounts, including suggested research questions and examples, see Phase 2 – Implementing monitoring & collecting data (social media listening tools) and the ‘Online campaigning’ chapter in the Online campaign: Analysis and Research section.

2 - Political advertising

This area of assessment aims to understand how contestants and other stakeholders use political advertising on social media. However, lack of available data may severely limit the depth of analysis in this area. It is a specific sub-area of the online campaign that focuses on paid or sponsored content, where money is spent to promote messages to selected audiences.

First of all, assess if there are legal provisions for online political advertising and ask candidates, where possible, if they plan on buying online advertising, and if so, on which online platforms.

A further research area not covered here would be to understand the online political ad use by non-contestants. Most problematic content is usually not pushed by official candidates, so understanding non-contestants advertising is highly important. Such an approach would require analysts to search for candidates and parties as “keywords” rather than by official accounts. Then, posts campaigning for or against the candidate could be labelled and quantified.

Using such a keyword search approach is only possible using the Meta Ad Library API and not the Ad Library Report or Google’s Political advertising transparency report which only allows you to search by advertiser. For guidance on data collection in this area, including the use of Meta and Google ad transparency tools and the fields to export (impressions, spend, targeting, dates, creatives), see Phase 2 – Implementing monitoring & collecting data (Online political advertising tools). For analysis and interpretation of political advertising patterns and risks, see the ‘Political Paid Content’ chapter in the Online campaign: Analysis and Research section, which explains how these data can be used to answer questions about transparency, spending, targeting and potential misuse of state resources.

3 - Information Manipulation

Influence operations seek to shape public opinion and behaviour, including during elections, and they can use many different tools — political messaging, pressure on institutions, offline mobilisation, or digital tactics. When these operations take place in the information space, they manifest through information manipulation, meaning deliberate attempts to distort, influence, or restrict the information voters can access.

Information manipulation includes several distinct techniques: 1) content manipulation (e.g., disinformation, misleading framing, deceptive visuals), 2) behavioural or algorithmic manipulation (e.g., inorganic amplification, coordinated engagement, bot activity), and 3) information suppression (e.g., mass reporting, cyberattacks, platform-level blocking). These should not be confused with broader hybrid operations, which combine diplomatic, military, economic, cyber, or covert tools — sometimes including information manipulation but not limited to it. Crucially, identifying manipulation patterns in an election does not mean identifying Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI). FIMI is a behaviour category requiring attribution — determining that a foreign state or state-linked actor is behind the activity. Since election observation missions cannot conduct attribution, they should report observable manipulation techniques and impacts, not classify cases as FIMI.

Information manipulation can consist of different and integrated tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs, e.g. coordinated or lone inauthentic actors, click farms, trolls, bots and botnets, cyborgs, other forms of manufactured amplification, etc.). Information manipulation is multifaceted and often created in a coordinated manner across different online platforms. It could be observed not only during the campaign, but also on the election day and prior to/during the announcement of results.

Information manipulation has the potential to exploit existing societal polarisation, suppress independent and critical voices, generate confusion among voters, discredit fact-based information and undermine candidates, institutions, and vulnerable groups. Artificially generated content and dissemination may distort the genuineness of public discourse by creating an impression of widespread grassroots support for or opposition to a policy/issue or individual/group

One should distinguish between the information manipulation that is created and shared within a small like-minded group most likely having a limited impact on the electoral process, and the one that has a potential to harm the electoral process.

As identifying manipulated information is time consuming and difficult, the best approach is to first narrow down the content which must be examined by:

- Approach 1: looking at information that has been distributed or spread exponentially, that is with greater reach or interactions than would be normal

- Approach 2: monitoring actors known for spreading manipulated information and then follow the information trail from there

- Approach 3: looking for hashtags or keywords used to push manipulated content.

A mixture of approach 1, 2 and 3 is recommended in an ongoing, iterative process. Identifying information manipulation requires some trial and error with different approaches to see which of them yields the best result. After content has been identified via one of the above approaches, one should then seek to prioritise content for deeper examination by asking “does it matter?”.

Sometimes a post identified as information manipulation may have reached a limited number of people, in relation to others with higher reach. Those should have priority. On the other hand, sometimes a large number of smaller reaching posts may also have influence on the election. Combining the 3 approaches above is the best way to try to account for all those possibilities.

To identify potentially relevant cases, SMAs can combine three approaches: (1) focusing on content that spreads far beyond normal reach and interactions; (2) monitoring actors already known for spreading manipulated information; and (3) using targeted keyword or hashtag searches to surface narratives of concern. Detailed guidance on how to operationalise these approaches is provided in Phase 2 and in the ‘Content Manipulation’ and ‘Platform / Algorithmic Manipulation’ chapters of the Analysis and Research section.

4 - Derogatory Speech and/or Hateful Content

The identification of instances and volume of Derogatory Speech and/or Hateful Content (see Glossary) during the election is one of the areas of assessment for the social media monitoring project. In this area, the focus is on online content that attacks, demeans or excludes people because of who they are, especially on the basis of protected grounds such as religion or belief, ethnicity, nationality, race, language, gender, sexual orientation, disability or other identity factors.

The aim of this area is not to label all harsh or offensive political debate as “hate speech”, but to systematically capture identity-based derogatory or hateful content that may affect equality, participation, or safety in the electoral process. Content that is hostile but not identity-based may still be relevant for the mission, but is normally analysed under other chapters (e.g. negative campaigning, defamation, information manipulation).

The research on this subject can be carried out in a way similar to the Information Manipulation section, with 3 different approaches:

- Approach A: Monitoring hateful keywords – Identify instances of derogatory speech and/or hateful content via the keywords and/or hashtags that are used

- Approach B: Monitoring potential perpetrators, whether those are official candidate/party accounts or external hate communities

- Approach C: Monitoring specific candidates who may be targets of online hate to identify instances of Derogatory Speech and Hateful Content via comments and mentions (e.g., women, minorities, LGBT+, etc)

Based on political context and team capacity, choose the most appropriate method. You will already likely be monitoring candidates and parties, which will only require you to add an additional layer of analysis. Although, if feasible, monitoring hate communities perpetuating hate can provide an early warning for new hashtags or terms. In many countries, these communities exist on niche platforms, which are more difficult to monitor. Consider if the benefits of monitoring niche platforms outweigh the required manual work of shooting in the dark to identify perpetrators. Some factors to consider are if they could provide a worthwhile early warning for your monitoring or influence a significant portion of the population.

As usual, a combination of the 3 approaches may provide the best results.

|

|

Monitoring hateful keywords |

Monitoring candidates or parties for hate |

Monitoring hate communities |

Monitoring vulnerable targets of hate |

How |

Keyword search to identify posts which can be qualitatively and quantitatively analysed |

Monitoring of posts by official candidate and party accounts followed by qualitative and quantitative analysis. |

First identify actors in the hate community. Then, monitor those actors on an ongoing basis collecting posts and carrying out analysis. |

First identify 2-3 worthwhile targets. Then, monitor mentions of individuals using a keyword search and/or comments on that person’s social media accounts. |

Challenge |

This approach only works well for text-based platforms, like Facebook or Twitter. It will be less efficient to capture hate in images or videos. |

If you conclude an actual party or candidate post constitutes “hate”, this is highly relevant for the election observation. |

The challenge here is first identifying the “seed account to monitor”. Consider pre-monitoring using searches to create your list of relevant accounts. This may be time consuming, but tends to be fruitful. |

Depending on the tool used to collect the data and on the social media platform, comments may not be available for collection. |

The analytical framework for this area combines who is targeted (protected ground) with how they are attacked (type of expression), while the seriousness of each case is interpreted using the cross-cutting variables on online impact and potential to harm described in Phase 3. For detailed methods on identifying and analysing derogatory and hateful content, including lexicon building, monitoring perpetrators and targets, and coding examples, see the “Derogatory Speech and/or Hateful Content” chapter in the Online campaign: Analysis & Research section.

International Standards

Summary table of principles and main international standards:

| GENERAL PRINCIPLE | MAIN INTERNATIONAL COMMITMENTS/STANDARDS | AREA OF ASSESSMENT/OBSERVATION |

| Freedom of expression | ICCPR art. 19 CCPR General Comment No 34 | Content regulation, including hate speech, defamation, and disinformation |

| Right to political participation | ICCPR art. 25 CCPR General Comment No 25 | Information manipulation, including inauthentic behaviour, disinformation Political suppression, intimidation, threats Derogatory speech, hateful content Platforms’ transparency on recommendation and moderation algorithms, access to data for scrutiny, transparency reports. |

| Privacy and data protection | ICCPR art. 17 CCPR General Comment No 16 CCPR General Comment No 34 | Data acquisition and processing Micro targeting Profiling |

| Access to information | ICCPR art. 19 CCPR General Comment No 34 | Access to the Internet, including filtering and blocking Election information, including about campaign financing Voter education Media and digital literacy |

| Transparency | United Nations Convention against Corruption | Election-related advertising Sponsored content Information manipulation, including microtargeting, bots, fake accounts. |

| Equality and freedom from discrimination | ICCPR art. 3 CCPR General Comment No 18 | Derogatory speech, hateful content Incitement, suppression of certain groups of voters Net neutrality |

| Right to an effective remedy | ICCPR art. 2.3 CCPR General Comment No 31 | Election dispute resolution Social media platforms voluntary compliance measures Social media platforms’ reporting system and appeal mechanisms |

Monitoring and Collecting Data

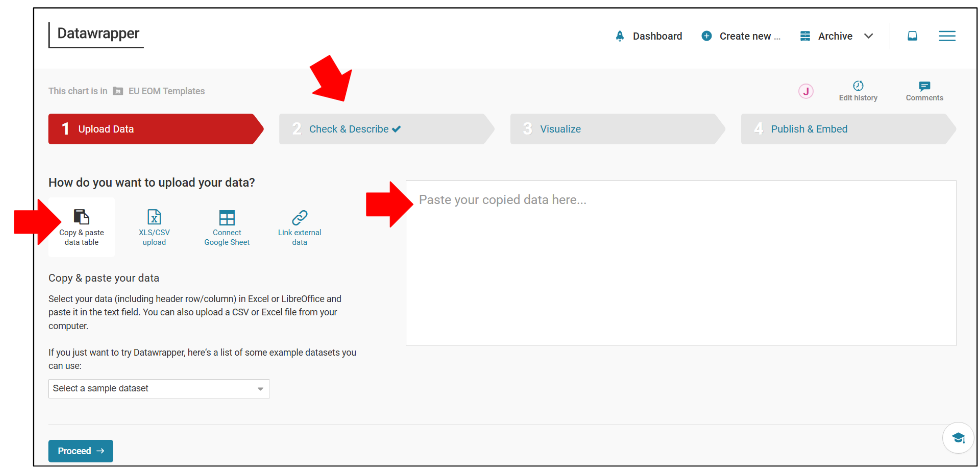

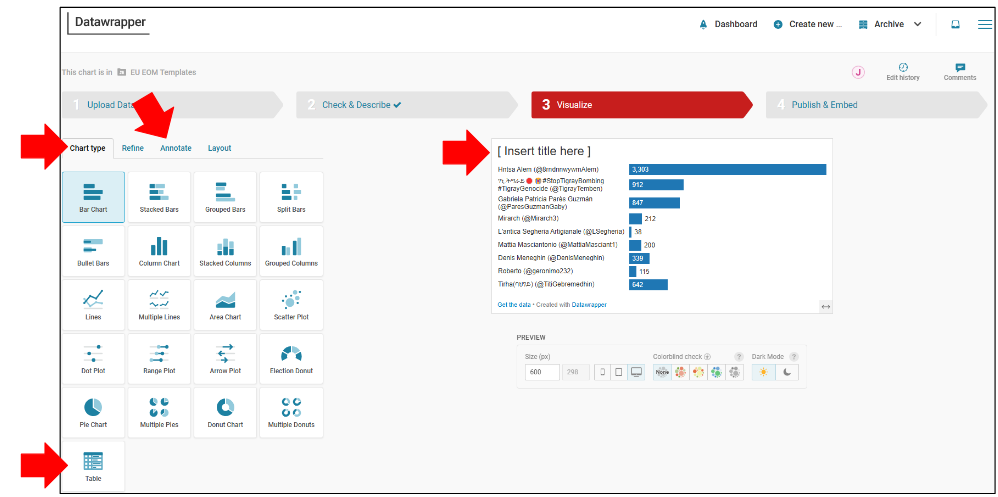

Implement lists and queries on a social listening tool

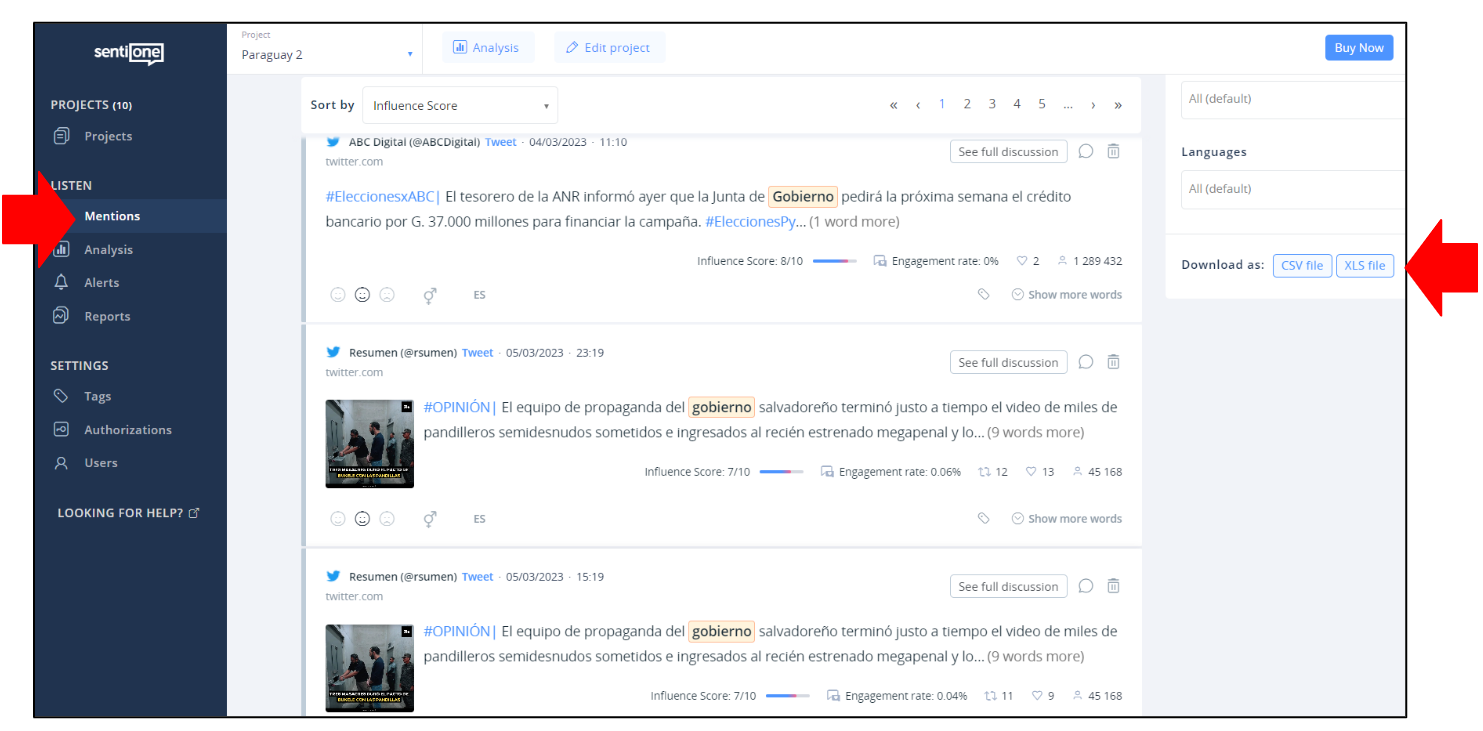

Most social media listening tools allow the implementation of lists or queries for monitoring content on social media. And, although each tool is different in the way that is done, the process is similar. In this tutorial we will use SentiOne Listen to exemplify the process of implementing lists and queries to monitor content on social media.

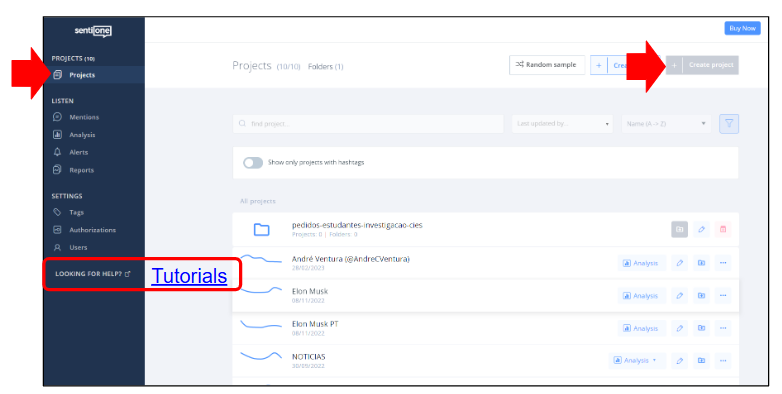

Implement lists on SentiOne

After you have registered and have access to a SentiOne Listen account, you can begin to compose a list of social media accounts on SentiOne by using the “Create Project” button. You can create a list for 10, 20, 30 or more accounts. Each project should correspond to a list for monitoring, but you can also monitor a single account, if that is what you want to track. If you have doubts on how to implement lists, please refer to the SentiOne tutorials on the "LOOKING FOR HELP?" menu.

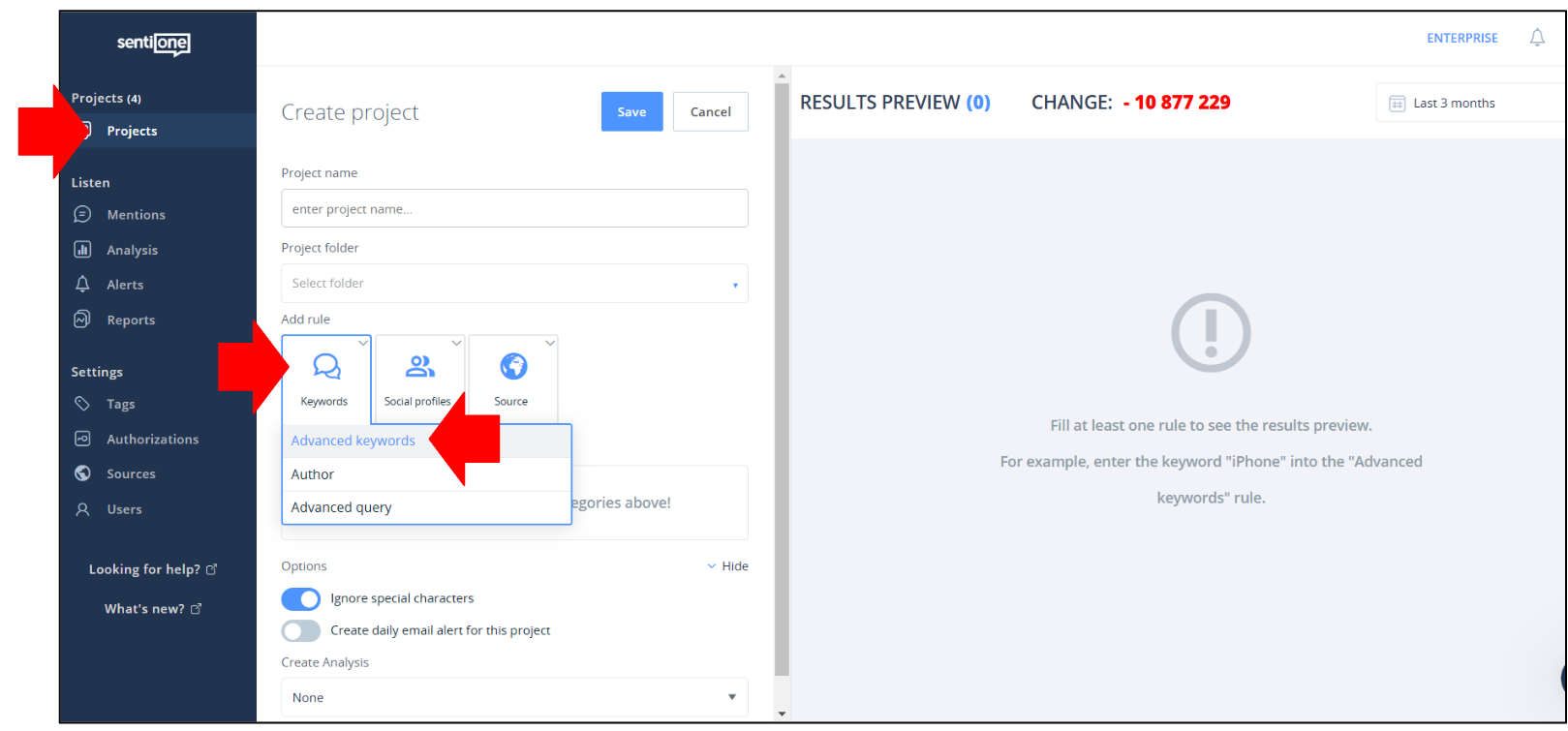

To implement a list on SentiOne proceed as follows:

- While in the "Projects" tab, click on "Create Project" and choose the option "Advanced"

- Then, hover to "Author" and enter the user name of the accounts that you want to monitor

- Check if the preview results on the right correspond to those accounts

- If so, give a name to the Project and save it

- You will be automatically redirected to the "Mentions" tab, where all your results will appear.

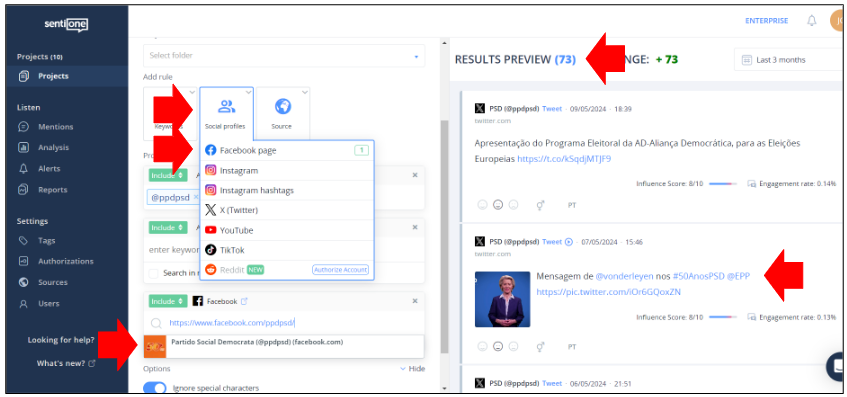

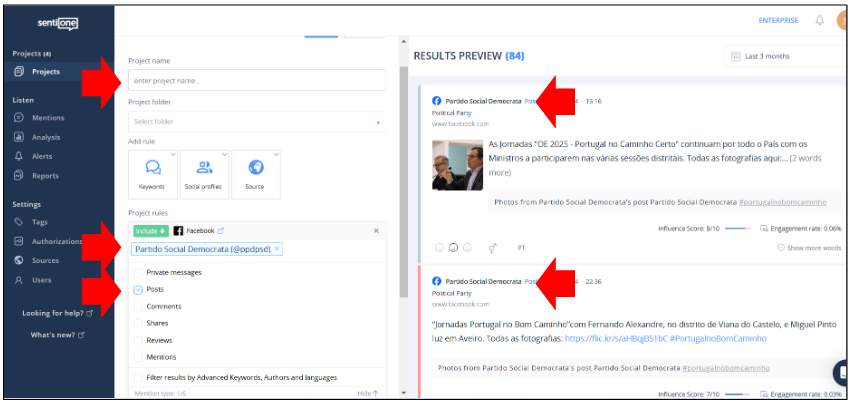

You can also implement lists on SentiOne using the "Social Profiles" function. To do so:

- While in the "Projects" tab, click on "Create Project" and choose the option "Advanced";

- Click on "Social Profile" and then choose the social media platform you want to monitor;

- Input the username or URL of the social media account you want to monitor and click on it when it appears. In this case you want just the posts published by that account, so use the drop-down menu to exclude comments, mentions and messages;

- Check the results preview to see if you're getting what is expected. If so, give a name to the Project and save it;

- You will be redirected to the "Mentions" tab, where all your results will appear.

When exploring social media pages and accounts to monitor on SentiOne, remember that this tool, like most other social media listening tools, only collects data from public sources, which may mean that some private accounts may not be trackable. In particular, Facebook pages and public groups will be available, but personal profiles may not, even if they are public and/or verified.

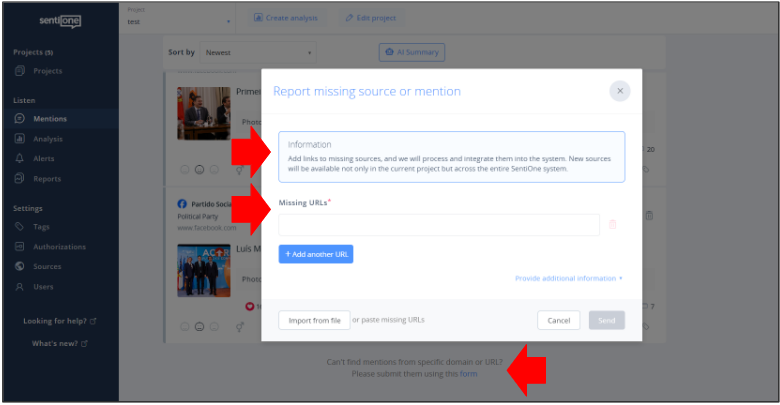

If you find social media accounts or social media posts that are not being tracked by SentiOne and should be, according to the rules above, you can and should report that lack of coverage to SentiOne support or use the specific reporting form that you can find at the bottom of the "Mentions" tab.

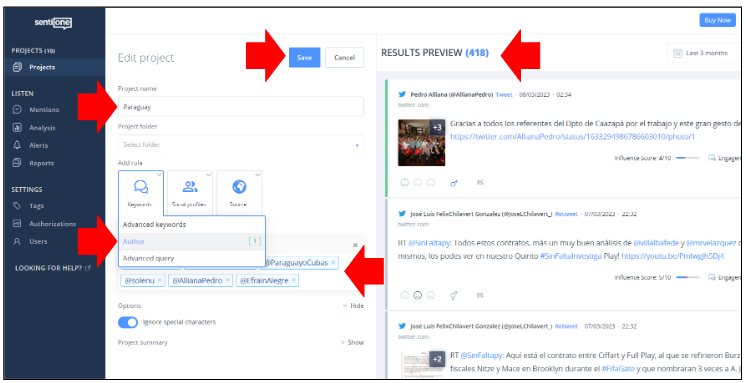

Implement queries on SentiOne

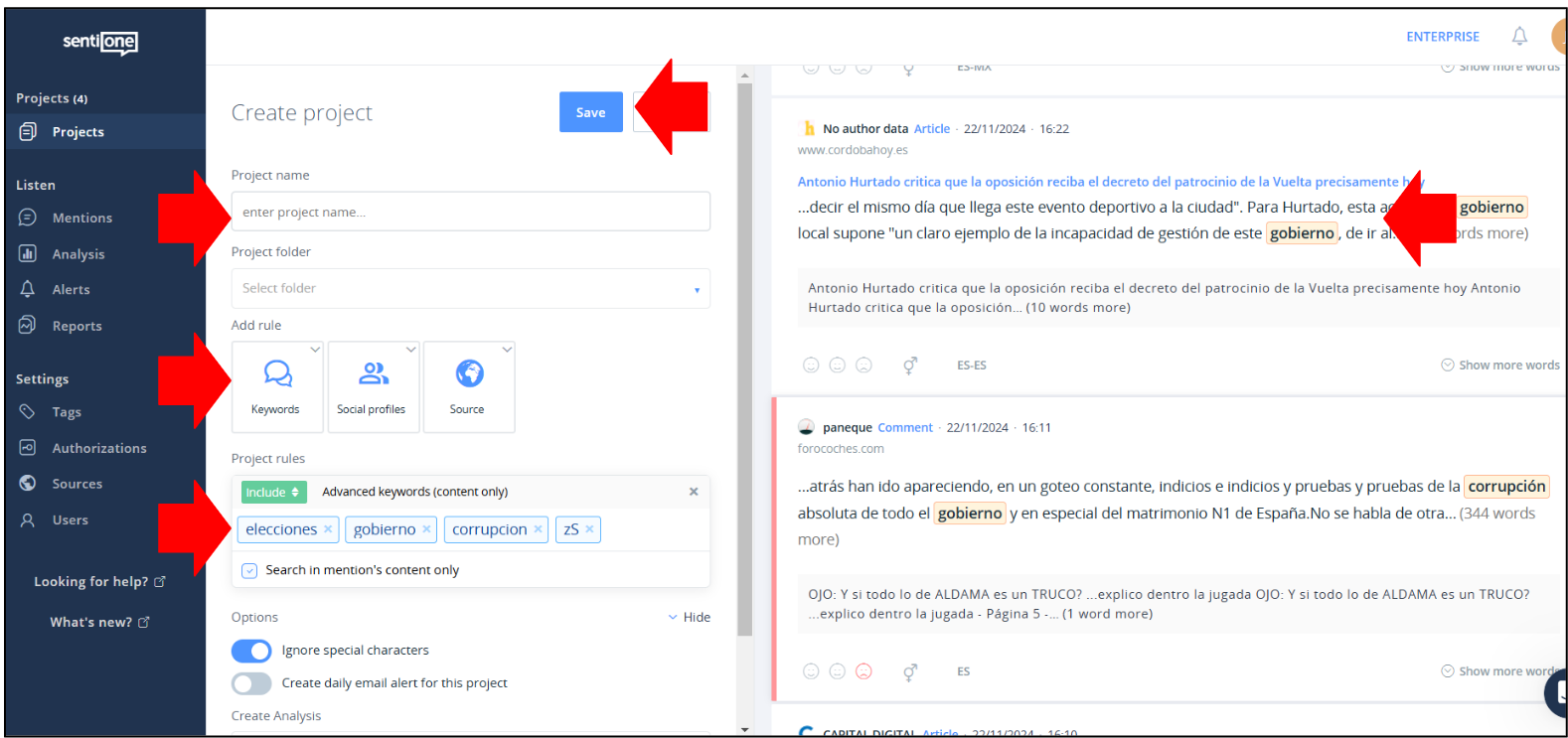

After you have registered and have access to a SentiOne Listen account, you can begin to compose a query on SentiOne by using the “Create Project” button. Remember that, whereas a list is to collect content only from the social media accounts that you select to be part of that list, a query is going to collect all the public social media posts that include the keywords that compose that query. If you want to track more than one query, each query should correspond to its own project. Best practices include composing one query for keywords directly related to the election (usually the names of the candidates are a good starting point) and one or two queries for keywords related to divisive and polarizing issues in the country. If you have doubts on how to implement queries on SentiOne, please refer to SentiOne tutorials on the "LOOKING FOR HELP?" menu.

To implement a query on SentiOne proceed as follows:

- While in the "Projects" tab, click on "Create Project" and choose the option "Advanced";

- Then, hover to the "Keywords" button and choose "Advanced Keywords";

- Insert one of the keywords in your query, press enter and verify in the preview if the results correspond to what you expected from that keyword. Pay special attention to see if the keyword is returning too many "false positives". If that is the case you should choose another keyword or refine it using search operators (see below)

- Repeat the process for your other keywords;

- If it is necessary to restrict the collection of posts to a given country or language, you can use the "Country" and/or "Language" filters in the "Sources" tab;

- Once the query is complete, save the Project. You will be automatically redirected to the "Mentions" tab, where all your results will appear.

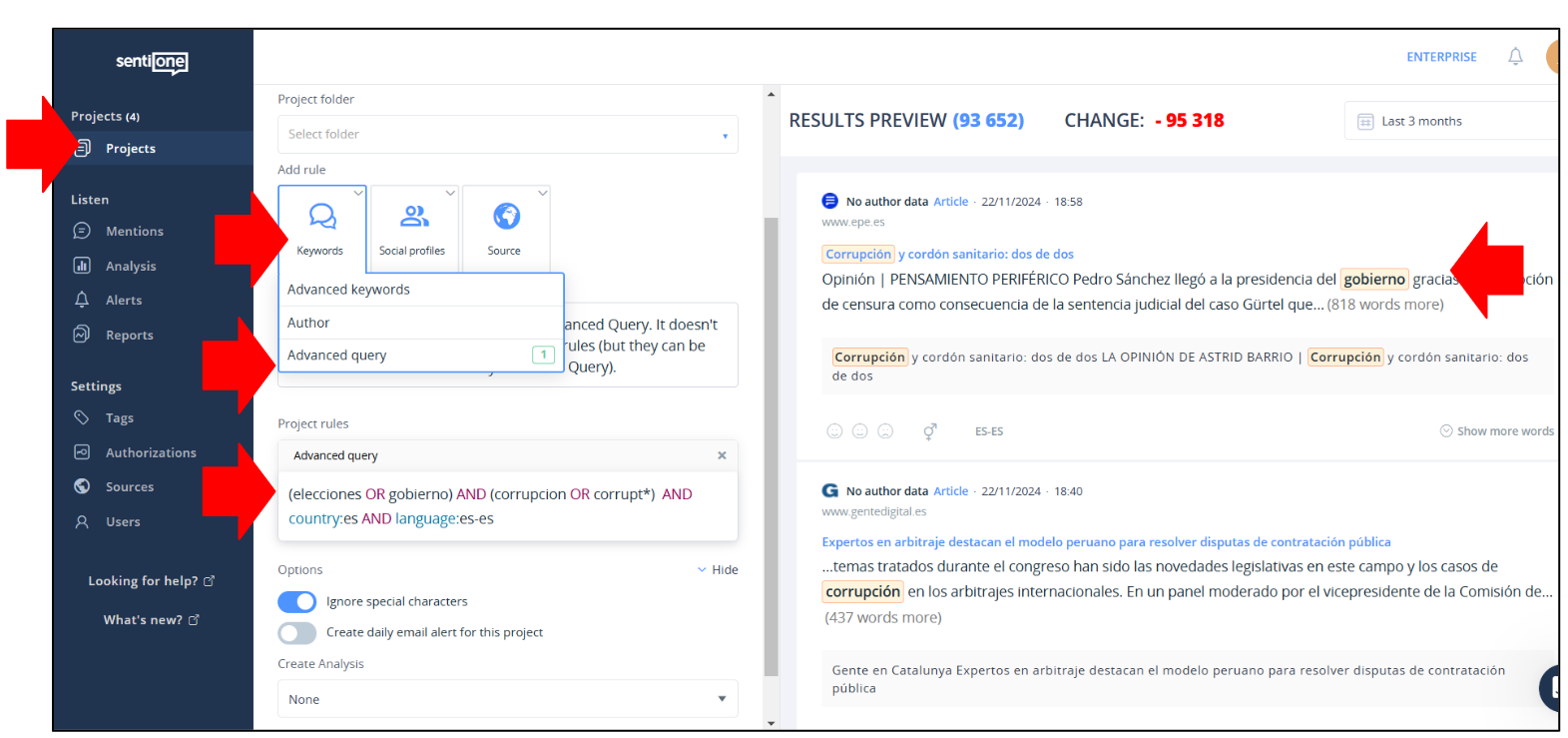

If your search is returning too many “false positives” (which is usually the case in the irst attempts at search) and you feel you need to refine your search query, you can use boolean search operators to better filter your search. If that is the case, proceed as follows:

- Hovering over the "Keywords" button, choose "Advanced Query" instead of "Advanced Keywords";

- Click on "Keywords" but then choose "Advanced Query" instead;

- Input the query that you want to use (an articulated set of keywords joined by search operators) and verify the results. You can see which search operators you can use in the help section of SentiOne. Like before, verify if your query is returning too many "false positives" and, if so, consider refining it further;

- If not, give a name to the Project and save it;

- You will be automatically redirected to the "Mentions" tab

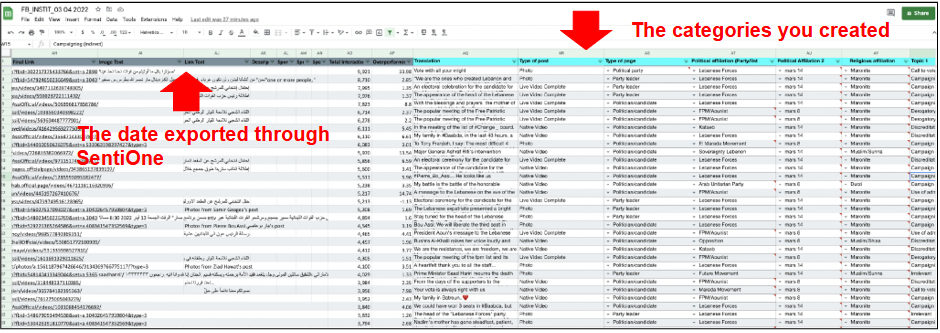

Collect data from SentiOne

After you have implemented lists and queries on SentiOne, and after you have assessed that the data is returning the results which should be expected, it's time to proceed to collect the data. Usually this is done on a weekly cycle (established according to the election campaign cycle), but data can be collected and analysed on longer or shorter cycles to provide context relative to specific days (as, for example, for campaign silence and election days).

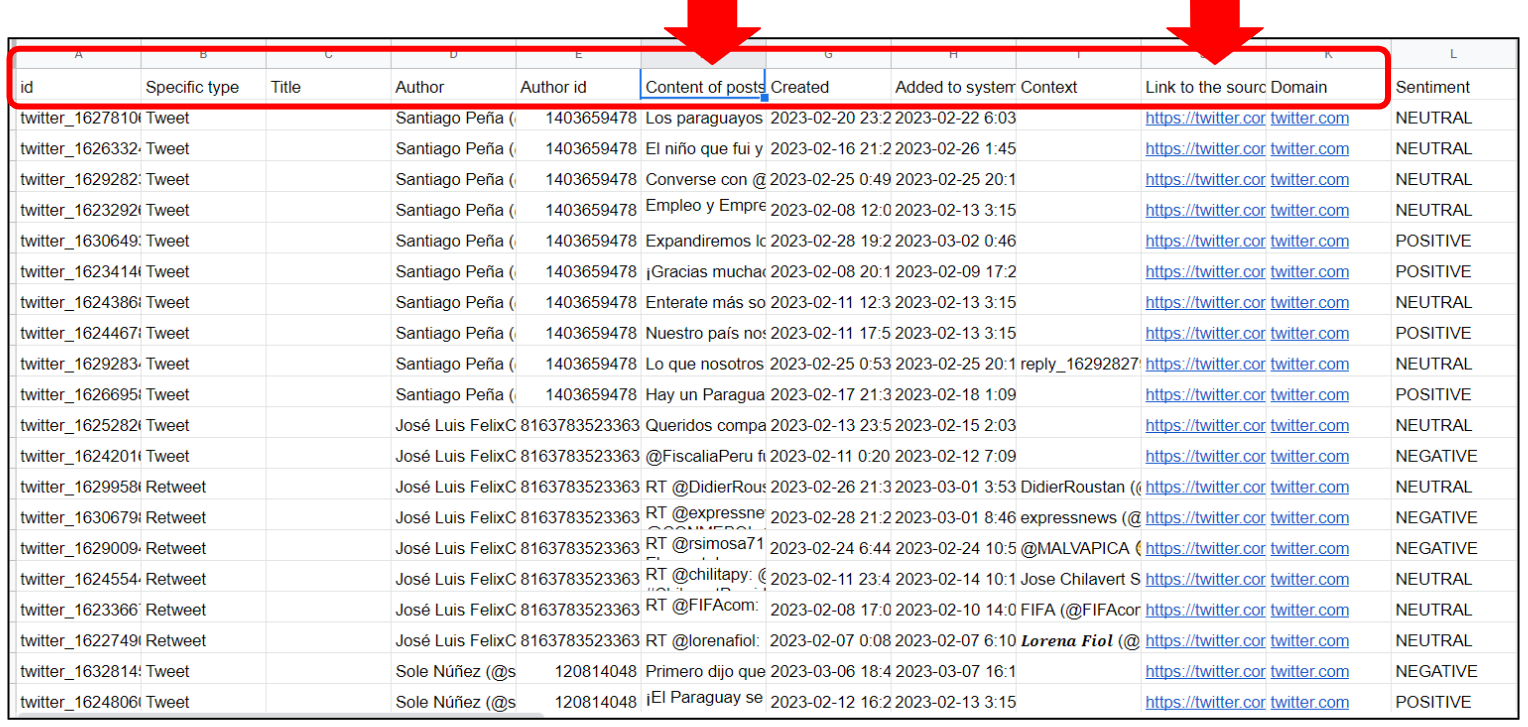

The data collected by SentiOne can be downloaded via two buttons at the bottom of the "Mentions" tab, one for XLS format (for Microsoft Excel) and another for CSV format (adequate for opening in several tools, including in Google Drive). Choose the format that suits better the environment where you will work with the data (Microsoft, Google or other).

Whatever the social media platform from which you are collecting data and if it comes from a list or a query, the columns of the XLS ort CSV file will be the same and may be ordered by date or "Influence Score" (an internal composed metric that combines how many times a mention has been viewed and shared, and how likely it is that has been seen). In the example below, each line corresponds to a post and each column to a data point about that post (author, content, date, link to the original, metrics etc). The data is ordered by "Influence Score" but can be reordered by any other criteria, namely by any other of the metrics available for the posts.

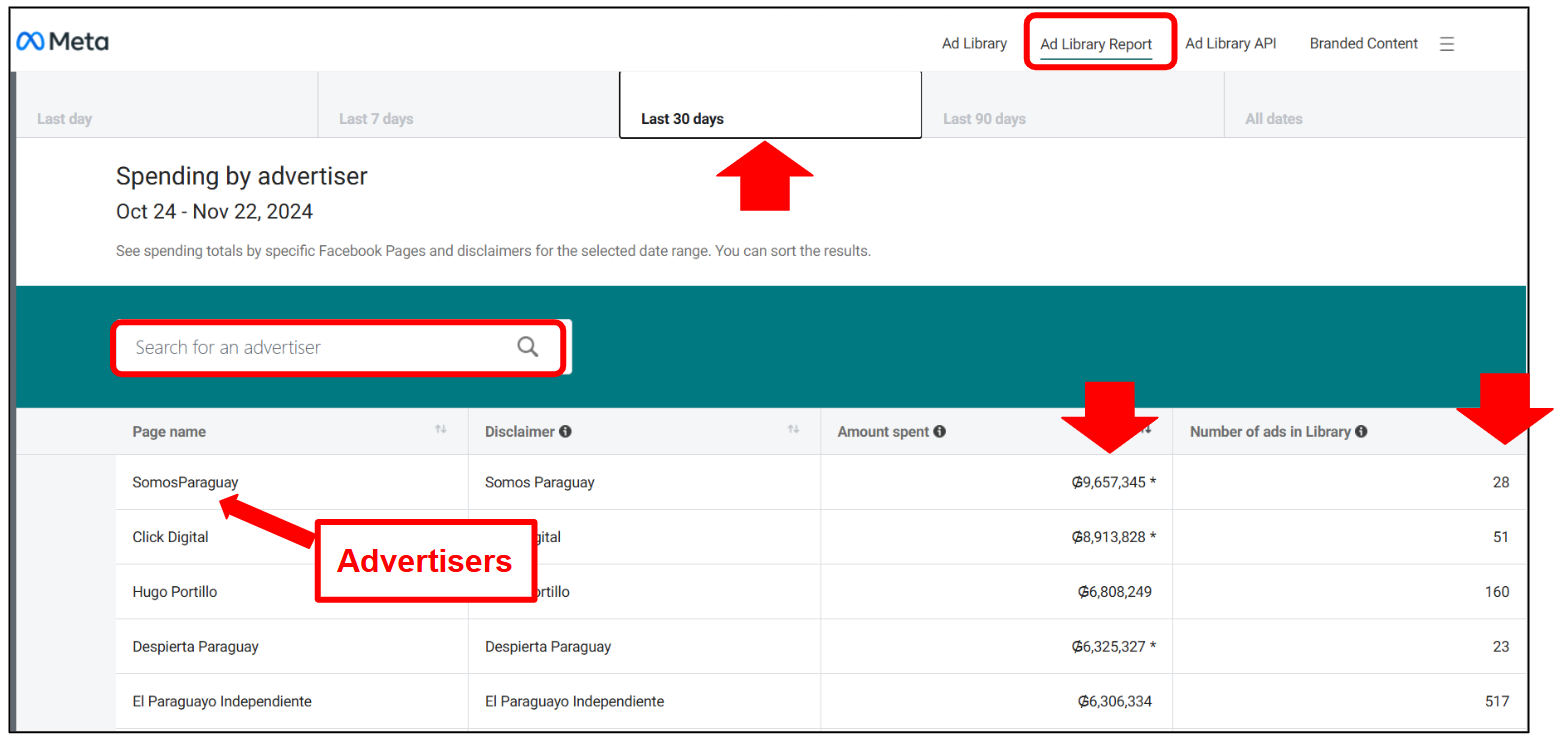

Online political Advertising Tools

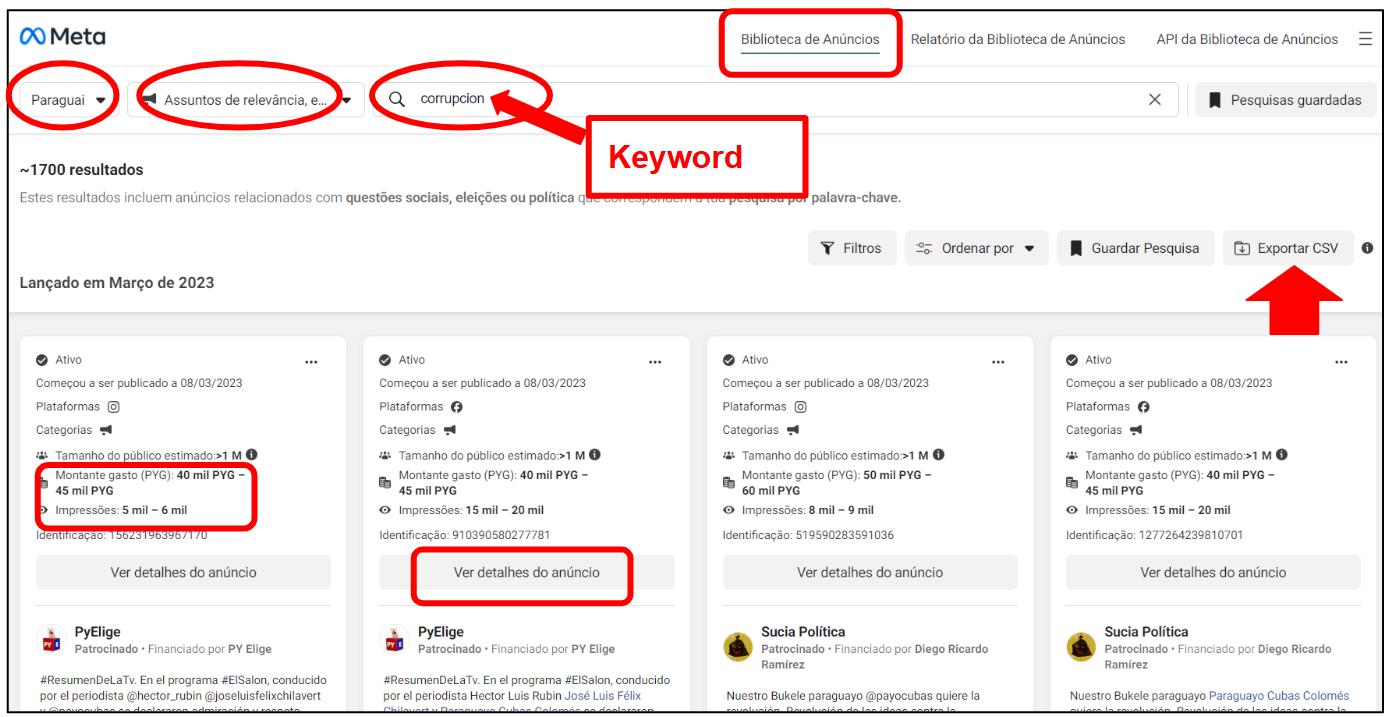

Track election ads on Meta and Google (if available)

Political advertising is one of the areas of assessment for Election Observation Missions. However, the tools to research and monitor online political advertising are limited and full information is not always available in a systematic and/or quantitative manner. Therefore, social media analysts may have to work with the information that is available. As of today, only Meta and Google provide systematic public dashboards and APIs for the disclosure of social and political advertising. Meta provides information about ads displayed in Facebook, Instagram and Facebook Audience Network; and Google provides information about ads displayed in Google (search and display network) as well as YouTube.

To track online political ads by official candidate or party accounts, the suggested method is to search for its official accounts on the available dashboards and compose a list, just as you did for social media monitoring. The dashboards that may have information available are the following:

To track online political ad usage by non-contestants or third-parties, the suggested method is to search for keywords or for the advertiser name, but that search functionality is only available on Meta Ad Library and Ad Library API. Neither the Meta Ad Library Report or the Google Ad Transparency Center offer keyword search functionality. That means you can only track political ads using the list method if you previously know which are the non-contestants that you wish to monitor or if you find them when searching. Local stakeholders may help in this.

Given these limitations, the suggested template for analysing political ads in EOMs should proceed in 4 steps:

Step 1 - Check availability in your country

Check if the Meta and Google ad libraries have data for the country that you're researching, assess if there are legal provisions for online political advertising and ask candidates (if available) if they plan on buying online advertising, and if so, on which online platforms.

Step 2 - Develop a list of official candidates and parties + select key contenders

Consider a threshold to limit your list if it is not possible to monitor all in the time period.

Step 3 - Data collection

Choose a subset of ads per party or candidate, potentially those ads with the most reach.

Manually download data per advertiser using Facebook’s Ad Library and Ad LIbrary Report or Google’s Ad Transparency Center.

Use the Facebook Ad Library API for more in-depth and automated analysis, if you can.

Step 4 - Data analysis

Work with the Excel or CSV files that are extracted from the dashboards.

From the Meta Ad Library Report you get aggregated information about the advertisers that were active on a given time period, including the number of ads circulated, the amount spent on those ads and the entity financing them. You can also search for specific advertisers (remember that on Meta the advertisers are the corresponding Facebook pages). If you can't find a specific advertiser that you're searching for, try enlarging the period to "all dates".

From the Ad LIbrary, you get specific information about each ad (either active or inactive), including the estimated audience, the amount spent (on each ad) and the impressions (views) gathered. As a significant limitation, Ad Library does not provide precise metrics for spending or impressions (views) but rather an interval for each ad (spend between X and Y and impressions also between X and Y). On Ad Library you can see either all ads by a given advertiser or search for ads that include a given keyword. Further details about each ad are also available as well as an option to export the selection as a CSV file.

Aggregated data on advertisers from the Meta Ad Library Report can be downloaded as a Zip file from the bottom of the corresponding page. That Zip file will include a CSV about the advertisers. Opened in Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets, the CSV will display the aggregated data on the advertisers.

Specific data on ads from the Meta Ad Library can be downloaded as a CSV file that will display specific data on the ads, including the relevant metrics regarding impressions (views) and amount spent, both as an interval rather than a precise value.

Also in the case of advertising, the RELEVANCE is given by the number of impressions an ad managed to get, because the higher the number of impressions the greater the number of people that presumably have seen it. In the metrics available for tracking the impact of political ads on social media, that is the best proxy for estimating the attention that a given ad message may have gathered.

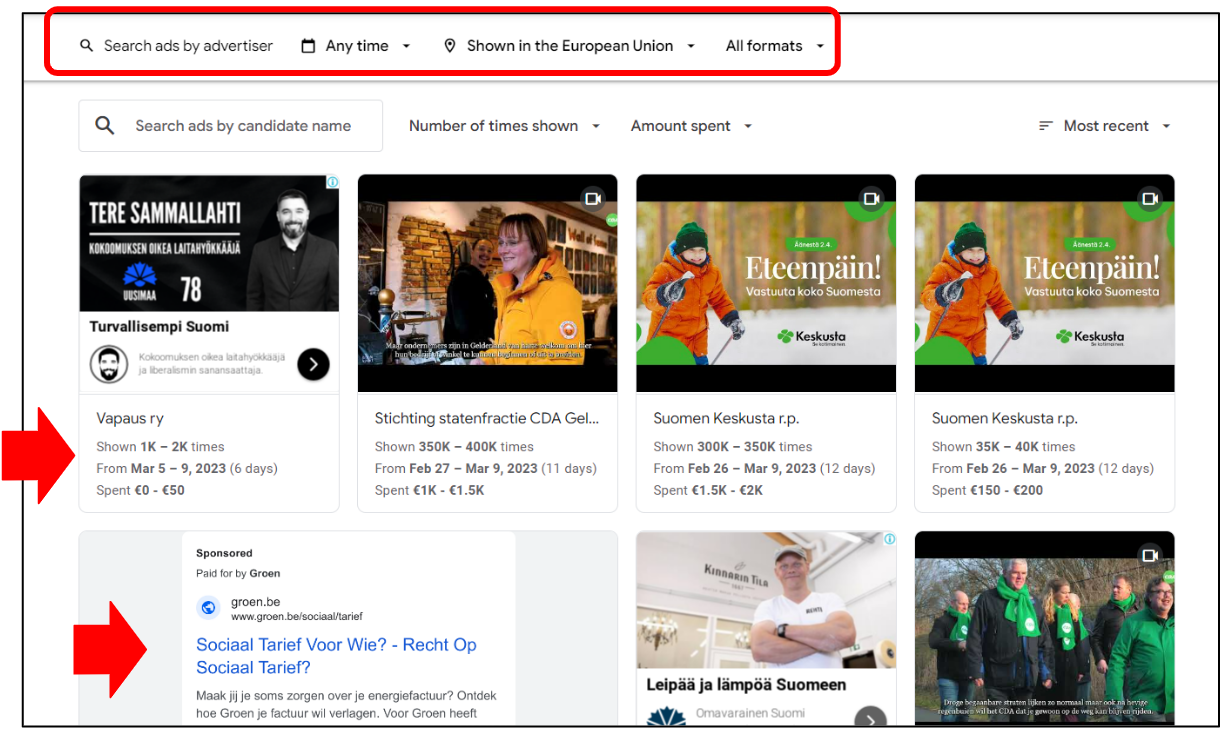

On Google Ads Transparency Center, information about ads circulated on Google (display and search) and YouTube is even more limited. You can:

- Search by advertiser to see total ad spend

- Analyse top keywords, spend per geography, targeting weekly spend, statistics

- View ad creatives by each advertiser

However, Google Ads Transparency Center also includes some limitations that are very relevant for the research:

- Limited data available (same as on Meta Ad Library, no precise values are given, just an interval of amount spent and impressions);

- Data on political ads available only for a very limited number of countries (currently Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, United States, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, United Kingdom, Taiwan, South Africa, India and all countries of the European Union;

- No clear indication for which ads were posted on YouTube or Google.

To track election ads on Google, you should look for advertisers corresponding to the lists that you are monitoring and track their ads on Goolge Ads Transparency Center. On this dashboard only aggregated data will be able to be downloaded, which means that data on specific ads (namely impressions and spending intervals) can be visible here, but will have to be manually collected, if necessary.

Given the limited data available, tracking online advertising in EOMs will have to resort to a combination of the quantitative data that is in fact available with the qualitative assessment resulting from consultations with local stakeholders on advertising strategies developed by the candidates or by the non-contestants publishing ads about the election.

Steps by area of assessment

Online Campaigning

Step 1 - Sample Selection – Define your lists of candidates and parties

First, you will need to come up with a general list of all candidates and parties that you would like to monitor. Consult lists of registered contestants from the electoral commission.

There is a high chance that you will need to limit your list to the top candidates and parties due to time constraints. For example, you may want to pick parties that maintain a large share of representation in the current parliament above a specific threshold. At the same time, you may want to consider if certain parties or candidates have shown a history of harmful online behaviour. Any decision on threshold should be clearly explained to report readers.

Second, you will need to define a timeframe relevant to the online campaign period. There may or may not be an official campaign period. It may also be worth monitoring after election-day to identify false claims regarding the election’s credibility, and results acceptance.

Third, depending on your data collection tool, you may need to find the exact social media handle per party and candidate. Determine if this step is necessary after identifying which data collection tool(s) you will use. Note this can be a time-consuming process, especially if you are looking at many actors.

Step 2 - Data Collection – Gather social media posts from the candidate and party accounts

Using the lists of actors from Step 1, you can start to gather all the social media posts from the selected candidates and party accounts. See Methodological frameworks section for guidance on how to collect data. Consider weekly data collection intervals so team members can label posts simultaneously to collection if relevant per step 3.

Step 3 - Data Analysis – Analyse the social media posts from the candidate and party accounts

|

|

Research question |

Means of analysis |

|

Question 1 (Easiest) |

Which party or candidate used social media the most for their online campaigning? |

Count the total number of posts per candidate and party. |

|

Question 2 |

Which social media platform did parties or platforms use the most during the campaign? |

Count the total number of posts per candidate and party per social media platform. |

|

Question 3 |

Which party or candidate did users engage with most on social media platforms? |

Count the total number of likes and shares per candidate and party (potentially by platform too). |

|

Question 4 |

Did parties or candidates use negative or positive campaigning techniques? |

Label posts as “negative”, “positive” or “neutral” and count the total posts. |

|

Question 5 |

Which topics did parties and candidates discuss during the campaign? |

Label posts by topic and count the total posts. |

|

Question 6 (Hardest) |

Did parties or candidates make false claims about the election or spread Derogatory Speech and Hateful Content using their official accounts? |

Label posts by the respective category and count total posts. |

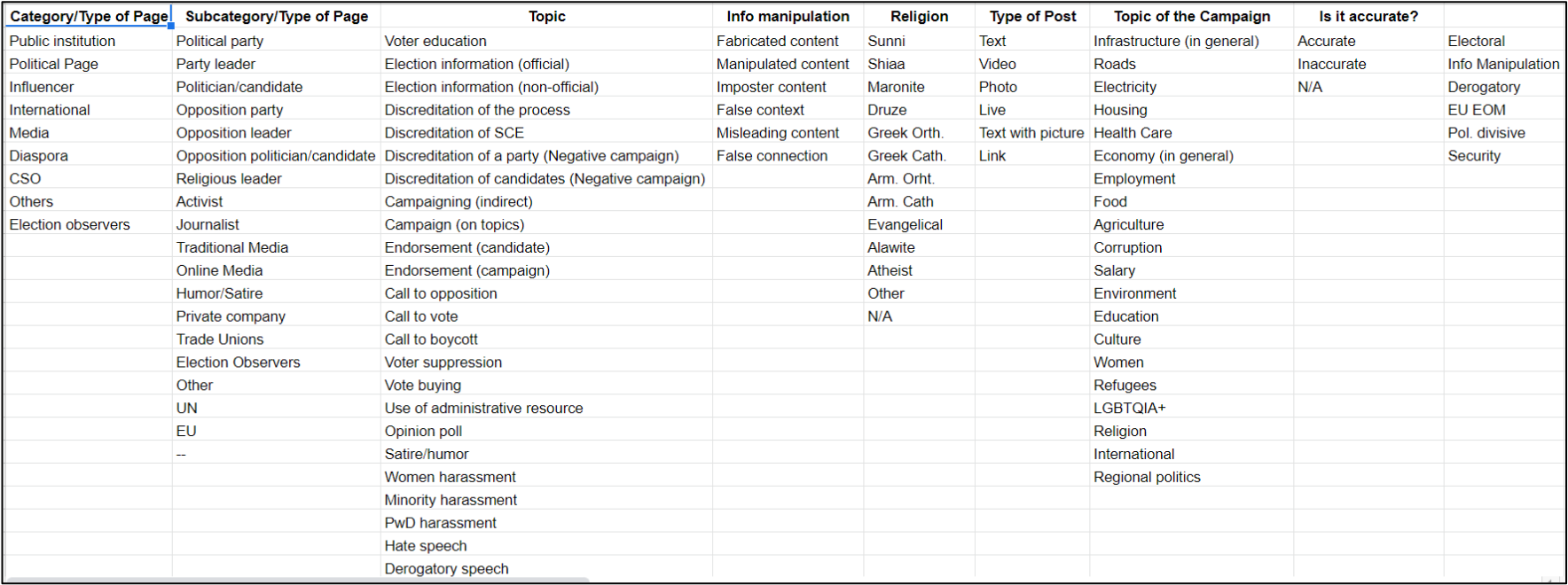

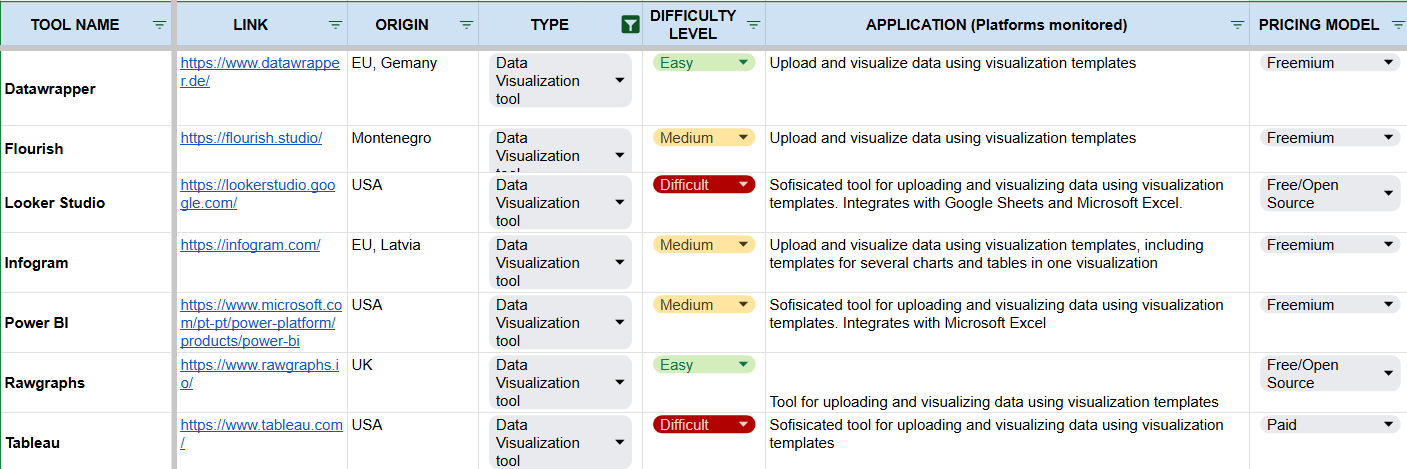

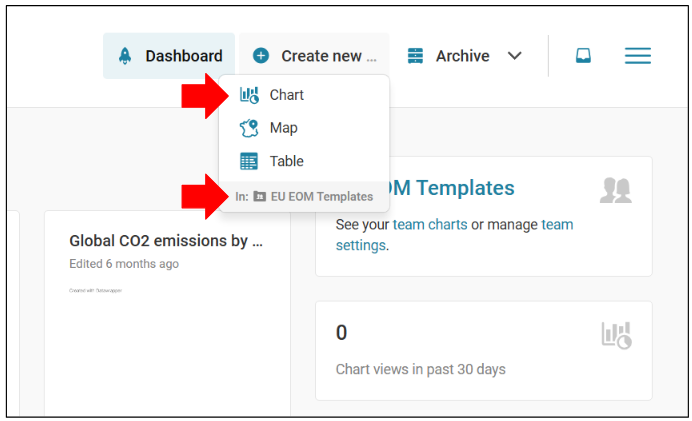

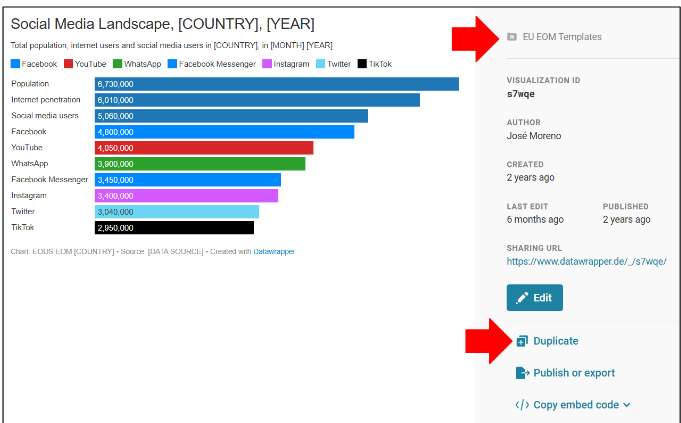

Some online tools for monitoring, collecting and analysing data offer the possibility of tagging or labelling social media publications according to previously defined categories. If so, that may be useful for the analysis. The categorization of the social media posts by candidiates and parties is described in the Monitoring Projects section. First, you should create a list of potential topics. Sometimes there are already useful websites for a given country that include the top political issues. Based on this list and qualitative information, you should limit the number of topics to 10 or so. Using your final list, you can develop a codebook with definitions for each topic and examples. Then you can label each post per topic, and the final data can be summarised and counted to understand the top-level trend.

Political advertising

Step 1 - Check if the tools to monitor political ads are available in the country

This step is important to decide if it is even possible to carry out analysis in this area of assessment.

- Facebook/Instagram: Meta Ad Library (search by keywords) and Meta Ad Library Report (search by advertiser)

- Google/YouTube: Political Ads Transparency Report (search by advertiser)

Step 2 - Develop your list of official candidates and parties

For this area of assessment, you will be monitoring the advertisements made by official candidates and parties. Consider a threshold to limit your list if it is not possible to monitor all within the time period.

Step 3 - Data collection

See Methodological Frameworks section for more information regarding the Meta Ad Library, Meta Ad Library Report, Meta Ad Library API and Google Political Ads Transparency report. Search for candidates and parties as “keywords” rather than by official accounts. Label and quantify posts campaigning for and against the candidate.

Non-programming (Facebook/Instagram and Google/YouTube)

Manually download data per advertiser using Facebook’s Ad Library report or Google’s Political Ad Transparency Report. Consider which intervals are relevant given time bucketing issues for some tools.

Programming Advanced Method (Facebook/Instagram)

If it is possible to use the Facebook Ad Library API, your analysis can go into more depth.

Take into account the limitations of the data collection from ad repositories:

- Facebook Ad Library is not available in every country

- Facebook Ad Library Report only allows to search by specific advertiser and only provides data with predetermined time frames predetermined, which might not align with your intended reporting period

- Google Political Add Transparency Report is also restricted to an even smaller number of countries

- Political Ads Transparency Report does not disaggregate results by Google property, such as YouTube or Google Search, for instance.

- Finally, neither Meta or Google provide precise values for ad impressions and amount spent. The data available expresses only an interval between the higher and lower values.

Step 4 - Data analysis

|

Question 1 (Easier) |

What was the total spend per party or candidate in the monitoring period? |

|

Question 2 |

Were any advertisements posted during electoral silencing periods? |

|

Question 3 |

Which demographics and regions were targeted by each candidate/party? |

|

Question 4 (More complex) |

What messaging did different candidates and parties use in their political ads? |

Generate summary statistics based on the data collected per each question. A challenge will be that data is sometimes available only within predetermined timeframes, which can create difficulties to have statistics corresponding to the desirable timeframe for election analysis.

First, draft a list of different topics or messages. Filter through a few random subsamples of ads per party or candidate to generate this list. Then carry out manual coding and add up the summary statistics. If there are too many ads to monitor, decide to only label posts above a certain threshold. For example, choose a certain number of ads per party of candidate, potentially those ads with the most reach.

Again, lack of available data may be a significant hurdle for the comprehensive assessment of Political Advertising on social media. Therefore, the social media analyst should work as much as possible with the tools available and consult with local stakeholders to "fill in the gaps" and guide the monitoring process. Also, bear in mind that Meta and Google do not exhaust the social media advertising landscape. Other platforms, like Telegram or TikTok, also allow ads, but do not provide a dashboard for the respective accountability. Telegram does not have such a dashboard and TikTok has an Ad Library but claims not allowing political ads (although some political actors have used TikTok influencers to convey their messages). Those approaches cannot be researched in a consistent and objective manner, but should nevertheless be under the radar of the social media analyst.

Identifying information Manipulation

Identifying online information manipulation may feel like searching for something in the dark at first. None of the available tools alone will be sufficient for a fact-based assessment on the presence of bots, trolls, fake accounts, and other manipulation techniques in online campaigns. Therefore, you often need to focus on some cases and conduct a full analysis of data retrieved via manual verification and OSINT tools to identify information manipulation techniques.

Reaching out to local social media analysts or OSINT experts who already work on the topic is highly recommended. They may already have lists of seed accounts for you to monitor or recommended keywords or places to begin your search.

Look for trending and viral content, which may be spreading unexpectedly fast. How much engagement has the content got in comparison to a typical post of this nature? If the tool or tools you are using have some metric to assess the overperformance of a post, try to use that metric. Otherwise, unusually high reach or total interactions may also be an indicator.

If your team has programming capacity, you can use PyCoornet or CooRnet to identify coordinated link sharing behaviour on a large sample of URLs. This is extremely useful to quickly identify any network behaviour for a more comprehensive picture. But note that a qualitative check is always needed when using these tools because coordinated activity can also be used for positive purposes as well, as, for example, when an electoral management body makes an important announcement about the election that is widely shared.

Develop a list of actors known for spreading manipulated information. You can compose this list following an iterative search on key divisive keywords in order to identify the actors that repeatedly and with greater reach address those key divisive issues. It may also be useful to look in the comments sections of known actors to identify actors that may be consistently spreading manipulated information.

The challenge with this approach is to have a transparent and consistent method to identify such actors known for spreading information manipulation. If that is not the case, the neutrality of the research may come to be questioned. Being transparent about the method used to identify those actors and about why they were identified is paramount to prevent that.

Look for hashtags or keywords used to push manipulated content. This approach leverages the fact that to spread information, the content creator must enable it to be found. Knowing the often “coded” vocabulary of troublesome movements or ideologies is useful here. For example, the use of polarising or divisive terms or language tends to be associated with manipulated content. If you follow those terms or language, you will be closer to identifying that kind of manipulated content.

Analysing information manipulation

If content is assessed to have received more engagement than expected, has been shared in diverse environments (i.e., groups), and has spread to different outlets (i.e., platforms), then it can have an impact on opinions and thus elections. This may be a useful threshold to consider when narrowing down your sample of posts to analyse from the previous section.

Analysts may then choose to investigate that content further using OSInt practices. They may also decide to code content for specific narratives to draw top-level conclusions (guidance on how to develop and use a codebook are also described in the Monitoring Projects section). It may be possible to draw some conclusions about the type of actors spreading such content (e.g., gossip pages, groups favouring a certain party); however, analysts should ensure their data or investigation is conclusive before quoting it in the reports. Remember that your analysis should always result from consistent, objective and transparent criteria.

Investigate suspicious accounts. Is the content being shared via suspicious groups? Checking the group’s history can also indicate if the group may have been setup only for spreading disinformation. Changes in admins, group name, creation date, and unusual follow/member demographics should all be checked.

Programming helps here, but some of this can be gathered manually, especially unusual follow/member demographics. Account or group names will often, although not systematically, indicate their character, e.g. their political leaning. Also, examine groups/accounts for shared administrators, followers or members to determine if they form a community.

While researching for information manipulation Datajouralism.com guides on Investigating Social Media Accounts and Spotting bots, cyborgs and inauthentic activity may prove useful.

Verifying specific posts may be necessary in your monitoring, although it will be time consuming to carry out a thoughtful, solid investigation into many posts. Consider testing average time required for your team to investigate a post to determine a realistic sample size for this area of assessment. See some useful resources:

- Bellingcat’s Beginner’s Guide to Social Media Verification

- Deutsche Welle’s curated guide to fact-checking and resources

- DRI’s Guide to image and video-based social media

- Also, check out the "Useful Resources" section in this Toolkit

Consider how many people have actually engaged with the content. If you find that a post is sharing false or misleading information, it would be important to know how many people that information may have reached. If it only reached 1 person, the potential harm of such content is less than if it had reached 1 million people. You can check metrics about the posts - namely reach and/or interactions - to try to assess how much attention that post has garnered. This information is also available in the .csv files you are collecting.

Understanding common narratives and tactical shifts is highly interesting. However, this method will require manual coding of a selected sample of false or misleading posts. If you are already planning on manually coding a selection of posts as false or misleading, this would be an easy and highly useful element to add to your analysis.

Create a list of false or misleading narratives based on qualitative research and a first review of false posts. From this, make a coding guide with clear definitions and examples for each category. Label posts accordingly and add more narratives to your master list as they come up. You may want to include specific categories for false information that specifically target electoral integrity. It may be useful to consider CT members such as Political Analyst and Election Analyst and social media companies’ policies when defining your categories.

For this, it may be useful to take some inspiration from the election policies set up by social media platforms to moderate content online, like these examples:

Once the posts are labelled, analyse top level summary statistics to understand which narratives were most important. Furthermore, how did the narrative shift over the campaigning period? Are there any feedback loops between niche accounts spreading such narratives and mainstream actors?

In order to identify and analyse information manipulation, try to follow these practical tips for guidance:

- Instead of tracking all the posts in one given social media platform, track only the most relevant. Those will most probably include disinformation content that may be relevant in the electoral process.

- Identify the narratives that, in each country, are more divisive and polarising. Those narratives may lead to information manipulation activities and/or derogatory speech and hateful content.

- It is not as important to focus on attribution (“the who”) as it is to explore the impact of the narrative on the electoral process (“the how”).

- Use monitored lists to identify repeated images, videos or narratives that can lead to coordinated inauthentic behaviour networks.

- When performing in-depth research on whether a post contains disinformation or misleading content, consider checking with local fact-checking agencies or searching fact-checking search engines.

- For more advanced search, use OSINT tools.

Derogatory Speech and/or Hateful Content

Step 1 - Define relevant keywords and actors

Your Derogatory Speech and Hateful Content lexicon should be made up of inflammatory language, particularly terms that could be used to target vulnerable populations. This list should be as widely encompassing as possible to gather many posts that can be analysed in a more refined way later. This process may be carried out through brainstorming with the local team and online research. But take into consideration that some SMM teams may be uncomfortable discussing hate speech and the associated vocabulary.